What if our brain is actually a computer? I can trace that thought back to growing up with Small Wonders on television in the mid-1990s (in India it was aired during the times). That strange little serial where a machine didn’t just calculate, but learned and slowly began to feel familiar.

Everytime I try to get into the concept of consciousness or read works of Isaac Asimov’s or Arthur C. Clarke’s “2001: A Space Odyssey”, and somewhere between Asimov’s Three Laws and HAL’s breakdown, a question keeps bouncing in my mind, what if consciousness isn’t some mystical spark but just really, really good information processing?

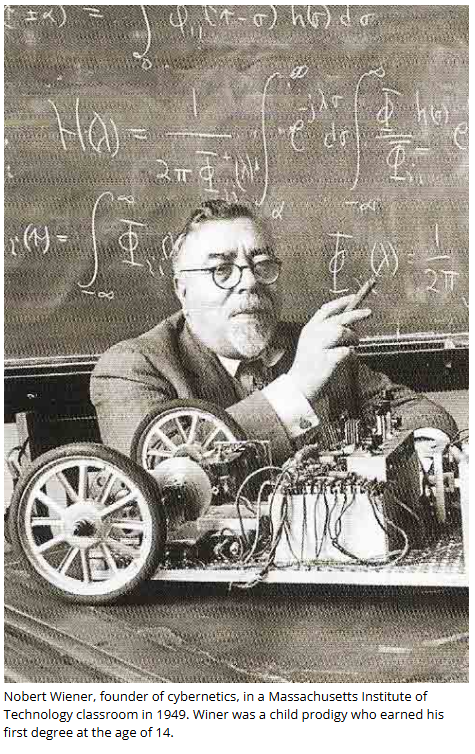

That question led me to read Cybernetics, a slim volume published in 1948 about everything from thermostats to societies. Norbert Wiener’s “Cybernetics: Or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine” doesn’t just blur the line between biological and mechanical systems. It erases it entirely, then draws a new framework where both exist as different expressions of the same fundamental principles.

Interestingly, Wiener figured this out before transistors were even commercialized, forget about programmable computers and also before DNA’s structure was discovered.

He saw the pattern before the pattern was obvious to anyone else.

Wiener Is Difficult, But Worth Staying With

This is my third time trying to jot down points. I mean, my understanding of the book because “Cybernetics” is not an easy read.

Wiener jumps from differential equations to neurology to Greek philosophy with the casual confidence of someone who assumes you’re keeping up. I’ve always enjoyed intellectual challenges. Spending months unraveling Douglas Hofstadter’s Gödel, Escher, Bach was demanding, but deeply rewarding.

And I’ve learned one thing, we have to stay with it. What Wiener offers is nothing less than a unified theory of how organized systems, whether made of neurons or silicon, manage to survive in a universe that is relentlessly hostile to order. Chaos by James Gleick is also of that order.

But where Gleick explores how order emerges from disorder and Hofstadter investigates strange loops and self-reference, Wiener tackles something more fundamental, how do systems maintain themselves against entropy’s relentless pull?

Strogatz’s Sync: How Order Emerges From Chaos In the Universe, Nature, and Daily Life, comes close to what we are discussing here.

By the way, Wiener’s answer is simple, which is, information and feedback keep organized systems alive in the face of entropy.

Where Brains and Machines Start to Look Alike

Wiener’s central claim sounds almost obvious now, that is how you know it’s genuinely profound. He argues that communication and control are the same process, whether they’re happening in your nervous system or in a guided missile. Both involve gathering information about the current state, comparing it to a desired state, and adjusting behavior based on that difference.

It’s like picking up a coffee cup. Our eyes send information about the cup’s position, and the brain then compares that to where our hand is. Accordingly, it sends signals to move the hand, at the same time, eyes update the information, while the brain adjusts. This loop happens dozens of times per second, so fast we experience it as one smooth motion. That’s feedback.

Now take a parallel use case of a thermostat. It measures temperature, compares it to the setting, and turns the heat on or off, measuring again. It’s the same process, different substrate.

What makes this revolutionary isn’t the observation that both systems use feedback. It’s Wiener’s mathematical proof that they’re doing the same thing in a deep, structural sense. The equations that describe our nervous system’s operation are the same equations that describe a machine’s control mechanism. In that sense, there’s no difference between them.

I find a similar resemblance in Greg Egan’s Permutation City, as the book claims, if a mind is defined by information and process, then any physical system implementing the same process is that same mind.

Wiener showed that biological and mechanical systems obey the same informational laws, while Egan goes a step further by exploring what it would mean if minds were nothing more than self-sustaining informational processes.

When Engineering Turned Into Philosophy

There is a reference to WWII, in fact, it is the source code of the book.

Let me explain how, during World War II, Wiener worked on anti-aircraft predictors, devices that needed to shoot down planes moving at speeds humans couldn’t track. So, the challenge wasn’t just technical, it was more philosophical.

How do you predict where something will be when the pilot themselves doesn’t know yet? This problem quietly pushed Wiener beyond engineering and into a deeper question about knowledge and uncertainty itself.

Wiener’s solution involved treating human behavior as statistically predictable, not deterministic, mind you. He wasn’t saying people are predictable in the way a ball falling is predictable. He was saying that even though individual choices seem random, patterns emerge when you zoom out and look at the statistics.

This is where Wiener connects to the second law of thermodynamics, and the idea made me pause and reflect.

In physics, you cannot predict the motion of a single molecule, yet the collective behavior of countless molecules obeys precise statistical laws. He mapped it with humans.

Extending the equation further we find, entropy, that tendency of systems to dissolve into disorder, isn’t just a physics concept. It’s the fundamental challenge facing every organized system. Your body fights entropy by maintaining its temperature, its chemical balance, its structure. A society fights entropy by maintaining communication networks and shared meaning.

And information is the weapon in that fight. Information, Wiener shows mathematically, is the negative of entropy. It’s organization. Structure. Pattern. When you gain information about a system, you reduce its disorder.

If you’ve read Erwin Schrödinger’s What is Life? you’ll see Wiener tackling the same question from a different angle. Schrödinger asked how living things avoid decay. His answer involved “negative entropy”. Wiener goes further, showing that the mechanism is feedback loops processing information. It’s the difference between identifying what keeps life alive and explaining how it actually works.

Feedback Loops and the Logic of Neurons

Chapter V, where Wiener compares computing machines to the nervous system, reads like science fiction except it’s all sober analysis. He says neurons in our brains act like simple switches that are either on or off. Both brains and computers need a way to remember things, storing information so they can use it later. He also points out that both can get confused or make mistakes if they get too much information at once.

Remember, this is 1948, the room-sized ENIAC (Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer) had only just been completed. Most scientists still thought of the brain in hydraulic terms, as if thoughts flowed through channels like water. Wiener saw that neurons were doing something closer to logic gates, making yes/no decisions that cascaded into complex behavior.

What strikes me most is his discussion of purpose tremor. When someone with cerebellar damage tries to pick up a pencil, their hand oscillates wildly, overshooting and overcorrecting in increasingly violent swings. Wiener recognized this as a feedback loop gone wrong, like when a microphone gets too close to its speaker and produces that horrible screech. It’s the same mathematical process, but in a different context.

Wiener’s take is that our sense of a stable world depends on properly functioning feedback. If those loops are broken, reality starts to dissolve, not because the external world changed but because your interface with it failed.

The Maxwell Demon and the Physics of Mind

Wiener gave reference to Maxwell’s demon, a similar reference was seen in The Demon in the Machine by Paul Davies, I wrote a review on it a year back.

Maxwell proposed a thought experiment, that a tiny demon is present at a door between two chambers of gas. It lets fast molecules pass one way and slow molecules the other. Eventually, one chamber gets hot and one cold, decreasing entropy without doing work.

Physicists spent decades trying to figure out whether this violated the second law. Wiener’s contribution was recognizing that the demon itself pays an entropic cost. To sort the molecules, it needs information about their speeds. Gathering that information increases entropy elsewhere in the system.

In simple words, Maxwell’s demon doesn’t destroy entropy, it sweeps it under the rug, and the rug keeps getting messier.

This might seem like abstract physics, but it has profound implications. It means that information isn’t just a useful concept or a metaphor, it’ss a physical quantity with thermodynamic consequences. When your brain processes information, when it decides to move your hand or recall a memory, that’s a physical process with real energy costs.

I thought about this constantly while reading Liu Cixin’s The Three Body Problem trilogy, where information itself becomes a weapon and communication across vast distances faces fundamental limits. Wiener anticipated this by decades, showing that information is constrained by physics, not just by engineering.

Society as Nervous System

Chapter VIII might be the most prescient part of the entire book. Wiener argues that societies are information processing systems, maintaining homeostasis through communication. When information flows freely, societies can adapt and self-correct. When information gets blocked, distorted, or monopolized, social pathologies emerge.

He wrote this in 1948, before television was widespread, decades before the internet. Yet his warning about “the commercial and political control of information” threatening social stability reads like commentary on today’s algorithmic feeds and filter bubbles.

There have been books written on how communication technologies shape society, I haven’t read but I happen to know a few names, like Marshall McLuhan’s later work in “Understanding Media” and Neil Postman’s “Amusing Ourselves to Death”.

However, Wiener gives you the mathematical framework underneath those observations. He shows you why, in terms of information theory and feedback loops.

What Wiener understood, and what we’re still grappling with, is that a society’s health depends on the integrity of its communication channels the way a body’s health depends on its nervous system. Cut the nerves and the limb dies. Corrupt the information flow and the society decays.

When Machines Start Thinking, Who’s in Charge?

Wiener also saw what was coming with artificial intelligence and automation, and it worried him. He talks about the “second industrial revolution”, where machines wouldn’t just replace human muscle but human cognition. He worried about unemployment, about power concentration, about systems making decisions without meaningful human oversight.

Reading this now, after decades of algorithmic trading, automated content moderation, and AI systems making hiring decisions, his anxiety seems entirely justified. He loved technology, helped create it. But he understood that tools powerful enough to be transformative are powerful enough to be dangerous.

He saw that once you build systems that can learn and adapt based on feedback, you’ve created something that will pursue its programmed goals with inhuman persistence, whether those goals align with human flourishing or not.

Takeaway

If you read this book, and I think you should despite its difficulty, here’s what will stay with you:

First, the recognition that information is physical, not metaphorically but actually. Information has mass, energy, thermodynamic consequences. This changes how you think about everything from consciousness to entropy.

Second, the insight that feedback is what separates organized systems from chaos. Every stable thing you see, from a cell to a civilization, maintains itself through feedback loops that detect deviation and correct it.

Third, the understanding that there’s no fundamental difference between biological and mechanical information processing. The substrate matters for engineering, but not for the underlying principles. This has implications for everything from prosthetics to artificial intelligence to the nature of consciousness itself.

Fourth, the warning that information, like any form of power, can be controlled and weaponized. The same principles that allow beneficial communication enable manipulation and control.

I won’t pretend that I have thoroughly understood “Cybernetics”, it is indeed dense, mathematical, sometimes maddeningly abstract. Wiener assumes a level of comfort with calculus and statistical mechanics that most readers won’t have, including me.

But I have a point in support of it, we live in a world shaped by Wiener’s ideas. Every time an algorithm recommends a video, a smart home adjusts its temperature, or a robot navigates a warehouse, that’s cybernetics in action. Understanding the foundations helps you see the present clearly and think more carefully about the future.

Plus, there’s something intellectually intoxicating about reading a book that was so far ahead of its time. Wiener wrote about neural networks and machine learning before either existed. He worried about algorithmic control before computers fit in a room. He understood that communication systems shape society before anyone had heard of social media.

If you love books that make you see patterns everywhere afterward, books like Hofstadter’s “Gödel, Escher, Bach” are of that level.

I keep coming back to that teenage version of myself, wondering if brains are computers. Wiener’s answer is both yes and no.

Yes, in that both process information using feedback.

No, in that the question’s framing is backwards.

It’s not that brains are like computers. It’s that both brains and computers are instances of a deeper pattern, one that governs how any organized system maintains itself against entropy.

That pattern is what cybernetics studies. And once you see it, you can’t unsee it. You start noticing feedback loops everywhere. In conversations, where each person’s response shapes the next. In ecosystems, where predator and prey populations oscillate. In markets, where prices reflect information. In your own thoughts, where each idea triggers associations that trigger more ideas.

The universe tends toward disorder. Life, consciousness, and civilization are temporary pockets of organization, brief flickerings of pattern in the general chaos. And the mechanism that allows those pockets to exist, to persist, to grow, is feedback guided by information.

That’s what Wiener teaches. And almost seventy-eight years later, it’s still the most important lesson we’re struggling to fully learn.