I’ve never been particularly good at math (at school) and when it comes to physics, the equations made me squint. And yet, I find myself completely captivated by the mechanics of how we fling those massive capsules filled with humans into space. And somehow bring them back alive.

There’s something deeply humbling about being a quark in the cosmos, the feeling that washes over me whenever I read or hear Carl Sagan and Neil deGrasse Tyson, and it returns again when I think about NASA plotting a course to Mars, tiny humans daring to cross an ocean of emptiness with nothing but physics and patience. This is just… overwhelming in the most beautiful way.

This thought is always lingering in my mind, and so this time I “dared” to hang-out with Ulrich Walter’s Astronautics: The Physics of Space Flight.

Huge shout-outs to Repository Poltekbang Surabaya for providing the book online. Astronautics was first published in 2007. Ulrich Walter, a former Space Shuttle astronaut and university professor, wrote this book with an aim to make the physics of spaceflight approachable for both students and working professionals.

So, the focus is heavily on the fundamentals, like how rockets work, how orbits behave, thrust, the beauty of thermodynamics and what all of this looks like in real missions. He often draws on examples from his own D-2 Spacelab mission, which helps ground the theory in real-world experience.

The book surely inclines towards semester courses but I decided to pick this one as I wanted to challenge myself. I’ll admit the book has tons of equations, it’s a technical manual, I know, so I had to take the help of AI tools to make them understandable.

It’s like the difference between someone showing you a blueprint versus handing you the tools and walking you through the build.

I Thought Fuel and Engines Mattered Most, But It’s The Weight

Walter opens with a thesis which states that space travel isn’t really about energy but it’s about mass.

Till now I was of the view that two things are super important for every space missions:

- fuel efficiency

- engine power

But the author states it’s the weight.

Every kilogram of payload demands exponentially more propellant. It’s like trying to climb a mountain while carrying all the food you’ll need for the descent, except the food weighs more than you do, and you need to carry extra food just to carry the food.

In the first chapter, under Total Thrust, he explained how The Saturn V, took humans to the Moon, and burned through 12.5 tons of propellant every second. Not per minute. Per second.

With this example, suddenly I understood why SpaceX’s obsession with reusability isn’t just about saving money. It’s about defying the fundamental mathematics that say getting to orbit shouldn’t be possible at all.

Walter doesn’t just put forward equations where thrust equals mass flow rate times exhaust velocity. He makes you feel why single stage to orbit vehicles are basically science fiction with our current materials. When he breaks down the structural ratio problem, the math becomes narrative.

So it’s not like learning equations for the sake of passing an exam, it’s more like being walked through the logic an engineer actually uses, step by step.

Letting Go Is the Only Way Up

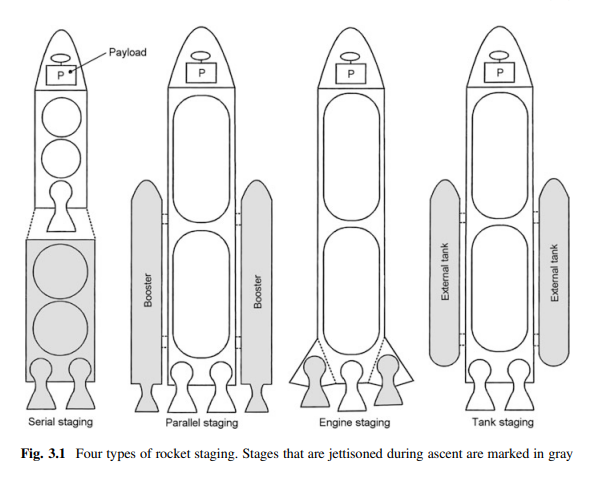

The chapter on rocket staging is like watching an exciting heist movie, even if you’re not familiar with how rockets work.

The idea is, you’ve got this huge goal of getting into orbit, but you’re stuck with the problem that you can’t carry unlimited weight. So the obvious idea is to get rid of anything the moment it stops being useful. It’s kind of like that scene in The Aeronauts, where they’re desperately cutting loose equipment from the balloon to climb higher. Every piece they drop buys them a little more altitude, but it also feels risky and irreversible. Rocket staging works the same way, letting go isn’t optional, it’s the only way up.

Walter explains that 90 to 95 percent of a rocket’s mass is either structure or propellant. Which means your actual payload, the thing you’re spending billions to launch, represents maybe 5 percent of what’s sitting on the pad. But then, by dividing the journey into stages, throwing away parts as you go, rocket engineers make it possible to send small but valuable payloads into space.

From Hot Gas to Liftoff to Rocket Thrust

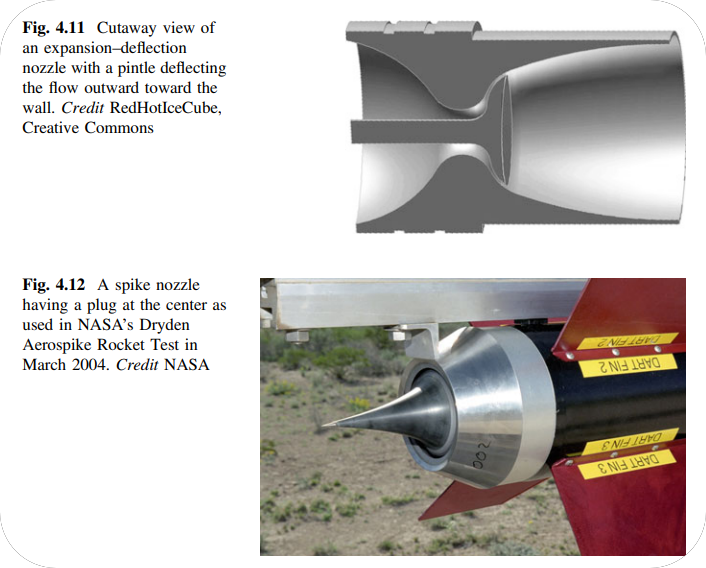

The section on rocket nozzles was not that overwhelming as a few years back I did research (at my level) on it.

Walter walks through how a Laval nozzle (named after the Swedish engineer Gustaf de Laval) converts hot, high-pressure gas into a focused stream that pushes things forward.

It’s all about taking the gas, accelerating it, and directing it so it can produce a strong push. This is similar to how gases naturally expand into empty space, but in this case, we control and speed up that expansion to make powerful rockets. So, something as simple as gas expanding into a vacuum is turned into the force behind some of the most advanced machines humans have made, like rockets and jets.

Walter is different from most technical writers because he emphasizes understanding things by intuition. Instead of just being able to repeat formulas, he asks if you can explain why something works in simple words, like talking to someone at a dinner party, without using math. The idea is that true understanding means you can make it clear and logical to anyone.

Orbits Aren’t Rockets Fighting Gravity

I liked this part of the book, Walter introduces orbital mechanics not as a series of problems to solve, but as a consequence of curved spacetime.

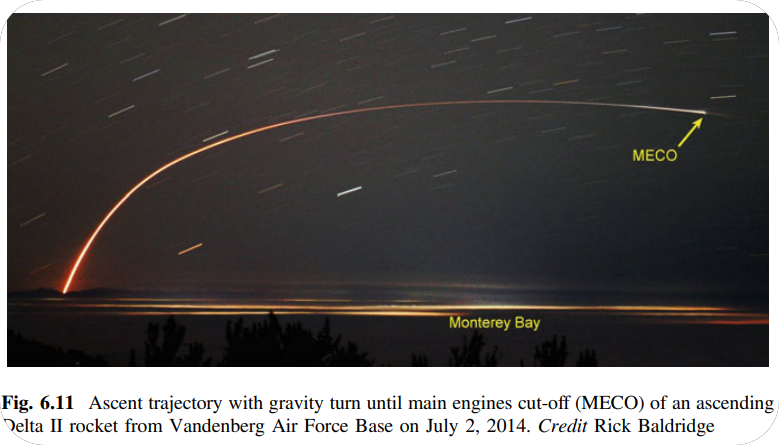

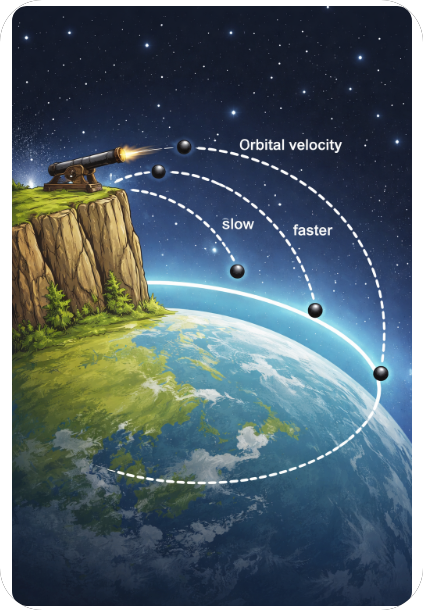

For example, when talking about orbits, it’s not about rockets zooming around in space. Instead, orbits are the natural routes objects take when they fall through curved space. A satellite in orbit isn’t battling gravity, it’s actually falling constantly but moving forward fast enough that it keeps missing the ground. It’s more about grasping the reason why things work the way they do, rather than just knowing the steps or calculations.

Imagine throwing a baseball horizontally from the top of a tall building. The ball will fall toward the ground because of gravity. Now, if you throw it fast enough, the ball will keep falling but also move forward. At a certain speed, the ground curves away beneath the ball as it falls, and the ball keeps “missing” the ground, moving around the Earth instead of crashing into it. That’s similar to an orbit. The ball is continuously falling toward Earth but keeps missing because it’s moving forward fast enough that it stays in a constant path around the planet.

The discussion of Keplerian orbits fits beautifully into this perspective. Once you see orbits as natural paths through curved spacetime, the familiar conic sections, circles, ellipses, parabolas, and hyperbolas, stop feeling like abstract geometry and start feeling inevitable.

Each shape is simply the result of how much energy and angular momentum an object has, as it falls:

- low energy gives you a closed ellipse, just enough energy gives a parabola that barely escapes

- extra energy opens the path into a hyperbola for flybys and interplanetary travel

Kepler’s laws then read less like empirical rules and more like reflections of deep conservation principles.

Seen this way, orbital mechanics isn’t about memorizing equations. It’s about recognizing that once spacetime is curved, these paths are the ones objects naturally follow.

Solar System is Full of Pulling Forces

Interplanetary travel introduces a problem. All the surrounding gravities are acting on the object:

- Sun’s gravity

- Earth’s gravity

- Mars’s gravity

The three body problem, Walter explains, has no general analytical solution. And it’s been tormenting physicists since Newton.

To deal with this, scientists use a trick called “patched conics”. Instead of trying to calculate everything at once, they split space into different regions.

- Inside Earth’s zone, they only consider Earth’s gravity.

- When moving further out, where the Sun’s gravity is stronger, they switch to focusing on the Sun.

- As they get close to Mars, they switch to considering Mars’s gravity.

This approach isn’t perfectly exact, but it gives very good results and makes calculations much easier.

This is about planning a space mission. The Rosetta spacecraft’s trip to a comet needed to carefully navigate around planets to use their gravity to help it along. It traveled billions of kilometers, passing close to planets to speed up or steer itself. Walter calls it a “billion Euro gamble” because it was a very costly and risky effort.

Liu Cixin’s The Three Body Problem uses this same physics as a plot device, though his version involves aliens and chaos theory. Walter’s treatment is more grounded but no less mind expanding. He shows how NASA actually does this, using the same math that proves the problem is theoretically unsolvable.

Rockets Work Better When They’re Already Going Fast

One of my favorite insights in the book is the Oberth effect. What I like about it is how unintuitive it sounds at first, but how simple it becomes once it’s explained, it says that the rocket engines are more effective when you use them while you’re already moving really fast, usually when you’re closest to the planet you’re orbiting.

It’s like pushing a swing, when it’s already moving faster, which in effect makes it go higher more easily.

In space, because energy depends on how fast you’re going squared, doing your burns near the planet or star gives you a bigger boost. That’s why space missions often perform their main engine burns when they’re closest to planets, it’s a smarter & more efficient move.

Remember the sling shot that was described and used in Interstellar, it’s something like that.

Coming Back to Earth Is Way Harder Than Getting to Space

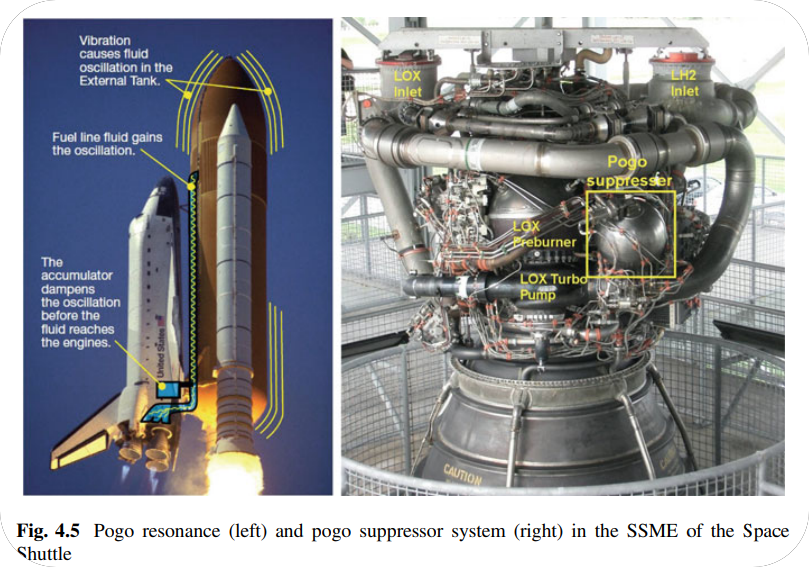

The chapters on atmospheric reentry are genuinely terrifying, just think, a spacecraft in low Earth orbit has about 33 megajoules of energy per kilogram. All of that has to be converted into heat. You can do it quickly and burn up, or you can do it slowly and spread the thermal load.

It’s like dropping a hot coal into a bucket of water. If you do it quickly, the water might splash and cause burns. But if you gently place the coal into the water, the heat spreads out gradually, preventing accidents.

The Space Shuttle handled this by coming in at a specific angle and sort of flying through the atmosphere instead of just falling straight down. Changing that angle helped control how much heat it experienced and how hard the astronauts were pushed by gravity. If the angle was wrong, really bad things could happen, either the shuttle would overheat, or it would bounce off the atmosphere and go back into space.

Similar calculations had to be done long before the Space Shuttle ever flew. During the early days of NASA, mathematicians worked out the exact re-entry paths for much simpler spacecraft, where there was even less room for error. This work is famously portrayed in Hidden Figures, which tells the story of three women at NASA, most notably Katherine Johnson, who calculated the precise angles and trajectories needed to bring astronauts safely back to Earth. Their math ensured that the spacecraft would slow down in the atmosphere without burning up or skipping back into space, laying the groundwork for the re-entry techniques used in later missions like the Space Shuttle.

Satellites Use Nature’s Forces to Stay on Track

When satellites orbit the Earth, they don’t follow perfect paths. The Earth itself isn’t a perfect round, it’s slightly wider around the middle because of this shape, the orbit doesn’t stay exactly the same, it gradually rotates over time, which is called precession, the J2 effect, caused by the Earth’s shape. Besides that, the Sun and the Moon tug on the satellites with their gravity, affecting the satellites’ paths. Also, sunlight creates a tiny push on the satellites, which may seem negligible but adds up over months and years, slowly changing the orbits.

Walter introduces these not as annoyances but as tools. Sun synchronous orbit takes advantage of natural gravitational effects to make sure satellites pass over the same spot on Earth at the same time each day, which is good for taking consistent images or measurements.

Another type, called frozen orbits, uses small orbit changes that happen naturally to keep the closest point to Earth steady, so the satellite doesn’t need a lot of fuel to stay in the right position.

The discussion of Lagrange points was particularly satisfying. Lagrange points are spots in space where the gravitational pull of two large objects, like the Earth and Sun, balance out. That means an object placed there can stay relatively in one place relative to them. The James Webb Space Telescope is positioned at one of these points called Earth-Sun L2, about a million miles from Earth. It stays there by moving along with Earth as it orbits the Sun, keeping itself in a kind of constant shadow or dark side. This spot isn’t perfectly stable, so the telescope needs small adjustments to stay in place, but overall it stays there quite well.

Walter is showing Jacobi’s integral, which is an important quantity that stays the same when studying how three bodies move when one is much smaller and doesn’t influence the others much. It’s one of the few things that remain predictable in a situation that can otherwise be very unpredictable or chaotic. The “zero velocity curves” are lines that mark the boundaries between areas where a spacecraft can reach or stay in and areas it cannot, acting like fences in space that limit where the spacecraft can go.

The Surprising Rule About How Things Spin in Space

One of the book’s best object lessons involves Explorer 1, America’s first satellite. Engineers tried to make it spin around its longest side (prolate) to keep it pointed in the right direction, thinking that spinning would help it stay stabilized. But instead of staying steady, it started flipping and tumbling in space.

The issue is that for an object to stay stable while spinning in space, it needs to rotate around its biggest middle line. If it’s shaped like a stretched ball (elongated), it is only stable if it spins around its shortest axis. In the case of Explorer 1, it was spinning around the wrong axis, which made it unstable. Over time, due to energy loss mostly from its flexible antennas, it started wobbling and tumbling until it settled into a position that’s more stable.

Walter calls this the “major axis rule”, and it applies to everything from satellites to footballs to ice skaters. When a skater pulls in their arms, they spin faster (conservation of angular momentum), but they remain stable because they’re rotating around their major axis.

This kind of insight, connecting spacecraft dynamics to everyday objects, is what makes the book sing. You’re not just learning aerospace engineering, you’re learning how the universe works.

Every Space Mission Comes Down to Delta-V

The main idea is about how space missions use fuel to move in space. “Delta v” means the change in velocity needed to perform different parts of a trip. For example, getting a rocket off Earth and into orbit takes about 9.4 kilometers per second of speed change. Moving from orbit to heading toward the Moon needs another 3.2 km/s. Every time the spacecraft needs to speed up or slow down, it uses some fuel, and the amount of fuel determines how much total velocity change it can do. So, planning a mission involves counting how much total delta v is available and how to use it efficiently.

Walter returns to this concept obsessively, and rightly so. It’s the fundamental constraint. You can have the most efficient engine, the best trajectory, the perfect launch window, but if your delta v budget doesn’t add up, you’re not going anywhere.

This framework transforms mission design from abstract planning into resource management. It’s why Mars missions require years of planning. Why asteroid redirect missions are feasible but Neptune flybys require decades. The delta v budget is the great equalizer, immune to marketing hype and political will.

Understanding Matters More Than Just Running the Numbers

Throughout the book, Walter maintains a peculiar insistence. Computers can calculate, but they can’t understand. They lack what he calls world experience, the physical intuition that lets an engineer spot a bad solution before running the numbers.

Anyone can plug values into the rocket equation. Understanding why staging helps, why the Oberth effect works, why orbits precess, that requires a mental model of how forces interact. It requires pattern recognition that comes from wrestling with the physics until it stops being foreign.

This approach reminded me less of science writing and more of Richard Feynman’s lectures. Feynman never just stated principles. He performed them, making you see the world through physics colored glasses. Walter does the same for astronautics.

Takeaway

After 400 pages, you’ll internalize things that seemed impossible at the start. You’ll understand why SpaceX lands boosters (staging in reverse to recover mass). You’ll know why the James Webb Telescope needed that specific orbit. You’ll grasp why reentry is the most dangerous part of any mission. More than that, you’ll develop a feel for the constraints that govern everything we do beyond Earth’s atmosphere.

- The delta v budgets.

- The mass fractions.

- The thermal limits.

- The orbital perturbations.

Instead of feeling infinite and mysterious, space turns into something you can break down into clear, measurable challenges.

This is empowering, every satellite overhead, every Mars rover, every Voyager probe hurtling toward interstellar space represents a victory done with physics.

“Astronautics: The Physics of Space Flight” isn’t leisure reading. As I said in the beginning I wanted to challenge myself, I’m able to get some theoretical knowledge. But this book won’t make me a rocket scientist for obvious reasons but it does excel in making me somewhat scientifically literate about rockets, which for me is a huge thing.

Also, reading this book was on my bucket list so it’s sort of one of the best things for me.

Walter stands on the shoulders of giants and invites us to climb up beside him. The view is worth the effort.