Each one of us, sometimes or the other has this weird habit or maybe obsession of checking if we’ve locked the front door or not.

You check once, locked.

Check again, still locked.

Third check.

Fourth check.

By the tenth check, you’re not actually discovering anything new, yet you can’t shake the doubt.

For people with obsessive-compulsive disorder, this scenario is almost… daily.

These individuals aren’t indecisive because they can’t think clearly. Instead, recent neuroscience research reveals that their brains struggle to update beliefs based on new information.

A study published this month in Nature Human Behaviour finally explains the mechanism behind this mental trap. Researchers from UCL, Oxford, and institutions worldwide scanned the brains of over 5,000 people while they made decisions, and found one crucial difference in how people with OCD process recent evidence.

How Normal Brains Decide

Before we understand what goes wrong, let’s understand how decision-making should work.

Let’s say you’re flipping a coin repeatedly, counting how many heads versus tails you get. With each flip, you gain new information.

A smart brain doesn’t weigh all flips equally, it trusts the most recent information most, which means, if you’ve flipped 20 tails in a row, the next flip still has a 50-50 chance, but the recent evidence tells you something about the pattern.

As per the researchers, it’s the “recency bias”, and it’s actually pretty smart. It helps us adapt quickly to changing conditions.

In this study, scientists gave over 5,000 people a game on their smartphones. They asked:

“Which hidden gem is more abundant across this grid?”

Participants could peek at as many hidden locations as they wanted before deciding.

What they discovered was that successful decision-makers don’t weigh all their gathered evidence equally. They lean heavily on the most recent information they found.

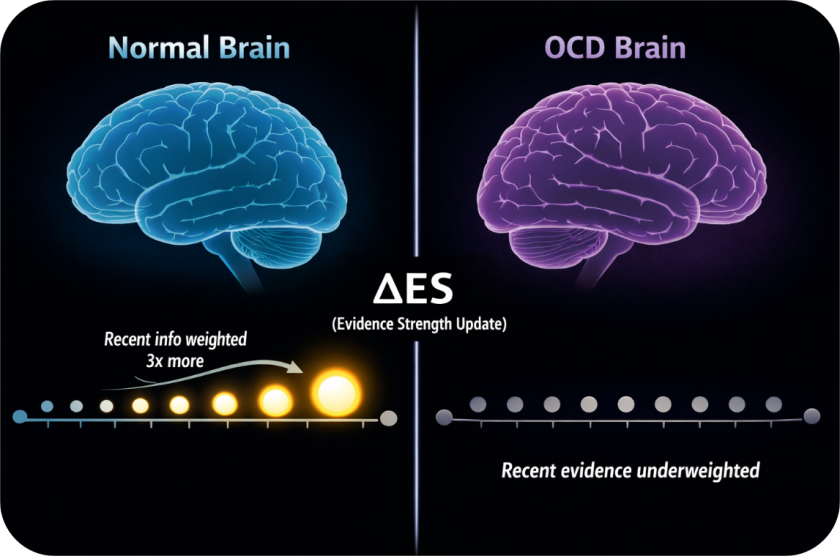

Specifically, they call this “evidence strength updates” or ΔES (delta ES), the change in evidence from the most recent discovery compared to what they already knew.

In normal brains, recent evidence has about 3 times the influence on decisions as older evidence.

When The Brain Doesn’t Trust New Information Enough

Interestingly, people with higher obsessive-compulsive symptoms showed a striking pattern, they weighted recent evidence much less strongly than people without OCD symptoms.

In their brains, recent evidence was only about half as influential as it should have been. So what they did was, they kept sampling information. In this case, checking the door again or verifying the alarm again or re-reading the message to make sure it made sense. As per, Tobias Hauser, the lead researcher,

“They’re not gathering more information because they’re smarter or more careful. They’re gathering more because their brains aren’t properly updating based on what they already found.”

Their decisions, however, were just as accurate as everyone else’s. They got the right answer just as often. They just took 2.5 times longer to get there.

It’s like having a calculator that works perfectly but doesn’t trust its own answers, so you keep recalculating, hoping the result will finally feel convincing.

The Brain’s Decision-Making Timeline

The researchers didn’t stop at behavior. They used advanced brain imaging (magnetoencephalography, or MEG) to watch the brains of 105 people, including patients formally diagnosed with OCD and generalized anxiety disorder, as they made decisions.

What they found was a fascinating window into how the brain processes information step-by-step.

The normal brain follows a sequence:

- First (400-600 milliseconds): The brain represents the basic factors, like how many choices you’ve seen so far, any time constraints, and all the evidence you’ve accumulated up to this point.

- Later (around 920 milliseconds): The brain computes the new information, the change from what you previously knew. This is ΔES.

The reason for the sequence is because you can’t calculate the change until you know what came before. It’s like algebra, you need to compute “B minus A” before you can understand the difference.

But in people with OCD symptoms, something was different.

The neural signal representing recent evidence updates (ΔES) was noticeably weaker in the mediofrontal cortex, a region crucial for evaluating information and updating beliefs.

Not weaker in a general way, specifically for the recent evidence signal. Everything else, their ability to accumulate evidence, their decision accuracy, their basic reasoning, remained completely intact.

A New Way to Understand OCD Decision-making

This finding overturns decades of OCD research.

Scientists previously thought excessive information-gathering came from “higher decision thresholds”, the idea that people with OCD simply set the bar higher before committing. Like saying, “I need to be 95% certain instead of 80% certain”.

But that’s not what’s happening.

Instead, the mechanism is about how beliefs get updated in the first place. If you can’t properly weigh new evidence, you never feel like you’ve truly learned anything new, so you check again.

This connects beautifully to a core feature of OCD, doubt and uncertainty that don’t dissolve with reassurance.

In case of an obsessive thought like, “What if I contaminated myself?” A person without OCD might check their hands, see they’re clean, and update their belief, “Okay, I didn’t contaminate myself”. New evidence (clean hands) successfully updates the belief.

But in OCD, that new evidence (ΔES) gets downweighted. The brain processes it less, so the original doubt doesn’t really shrink. The person checks again, hoping the next evidence will feel more convincing.

“It’s not that their decision threshold is wrong,” Hauser notes. “It’s that their evidence updating system is under-powered.”

It’s About Obsessions, Not Compulsions

The researchers also dug into clinical severity. They gave OCD patients a structured clinical interview and measured obsession versus compulsion severity separately.

The result was that the weakened evidence-updating signal (ΔES) correlated strongly with obsession severity (ρ = −0.475, P = 0.012) but not with compulsion severity (ρ = −0.205, not significant).

This suggests the mechanism feeds the obsessions themselves, the thoughts, rather than the compulsive behaviors.

Why does this matter? Because it points toward what might help. If the problem is belief-updating, interventions that retrain how people process new evidence might work differently than interventions targeting compulsive behavior alone.

It’s Not Just OCD

This mechanism isn’t exclusive to OCD. The researchers tested people across a full spectrum:

- Healthy controls

- Non-clinical individuals with low OC traits

- Non-clinical individuals with high OC traits

- People with generalized anxiety disorder

- People formally diagnosed with OCD

The weakened evidence-updating signal appeared in all of these groups, correlating with the severity of obsessive-compulsive symptoms, not the diagnosis itself.

A person with high OC traits but no OCD diagnosis showed the same brain pattern (just less extreme) as someone with clinical OCD.

This suggests indecisiveness and doubt driven by this mechanism represent a dimensional spectrum, not a distinct disorder. The question isn’t “Do you have OCD?” but rather “Where are you on the obsessive-compulsive symptom spectrum?”

It also means the finding might eventually help with indecisiveness in conditions that don’t get labeled “OCD”, like some presentations of generalized anxiety or even perfectionist paralysis.

What This Means for Treatment

The implications are profound and practical.

First, diagnosis clarification: If indecisiveness stems specifically from weakened evidence-updating, clinical assessment could potentially shift toward measuring this mechanism rather than relying on symptom count alone.

Second, targeted intervention: Knowing the mechanism opens new doors. Instead of broadly telling someone “stop checking” or “resist the urge”, you might target the specific neural process.

Some possibilities under exploration:

- Cognitive retraining: Explicitly practicing how to weigh recent evidence appropriately in low-stakes situations, potentially retraining the brain’s updating system.

- Brain stimulation: Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) targeted at mediofrontal regions has shown promise in OCD treatment. This research suggests it might work by enhancing the evidence-updating signal specifically.

- Pharmacological enhancement: Research on dopamine and serotonin systems continues, but this study hints that neurotransmitter systems affecting belief-updating might be particularly relevant.

- Digital interventions: Apps could gamify evidence-updating in ways that train the brain’s weighting system.

When The Brain Updates Too Much

While this research focused on excessive information-gathering in OCD, it raises an intriguing question about the opposite problem.

In psychosis and delusions, people often show the opposite bias, “jumping to conclusions” (JTC). They make decisions with insufficient information, forming strong beliefs from minimal evidence.

If OCD involves under-weighting recent evidence (ΔES), might psychosis involve over-weighting it?

The researchers hint at this possibility but acknowledge it remains unexplored. If true, it would suggest a beautiful symmetry, different mental health conditions might involve different directions of the same computational error.

Key Insights

The mechanism is specific, not general. People with OCD don’t have generalized indecisiveness. They specifically struggle to weigh recent evidence properly when updating beliefs.

It’s brain-based, not just psychological. The weakened neural signal (ΔES) in mediofrontal regions provides objective evidence of the mechanism, not just behavioral observation.

It works across diagnoses. The mechanism appears in OCD, GAD, high-OC non-patients, and even healthy controls, following a continuous spectrum.

It explains the obsession-doubt connection. Weakened evidence-updating explains why reassurance doesn’t work as it should, the brain isn’t properly integrating the reassuring information.

It opens new treatment targets. Interventions can now aim at retraining evidence-weighting rather than just suppressing behavior.

The Real-World Impact

Consider Maya, a fictional composite of people struggling with OCD-related indecisiveness:

Maya checks her email before sending it. Reads it once. Twice. Three times. The email is fine, she knows it’s fine. But the doubt creeps in: What if I missed something? So she checks again.

Before this research, therapy might focus on behavioral exposure (learning to send without checking) or thought restructuring (challenging the doubt thoughts).

Now, with understanding the mechanism, therapists might specifically help Maya retrain how her brain weights recent evidence.

“You’ve checked three times. Each time, the email was fine. That’s recent evidence (ΔES). Your brain should be heavily factoring that in. Let’s practice trusting that signal”. It’s not just exposure therapy. It’s mechanism-targeted training.

Takeaway

Indecisiveness has long been painted as a personality flaw or a character weakness in OCD. But this research reveals that it’s a computational problem in how the brain integrates new information.

In a way, that’s hopeful. Personality flaws are hard to change but computational problems can be retrained, targeted, even fixed.

The next decade might bring interventions so precise that they don’t just help people resist their urges, they help their brains update beliefs the way they’re supposed to.

And that changes everything about what’s possible for people stuck in the paralysis of doubt.

Frequently Asked Questions

Does this mean OCD is “just a brain problem”?

It means OCD has a specific neurocognitive mechanism that can be identified and potentially targeted. Your thoughts and behaviors matter, but now we understand the brain-level process underlying them. It’s not either/or, psychology and neurology work together.

If my brain under-weights recent evidence, how can I retrain it?

That’s exactly what researchers are now testing. Likely approaches include repeated practice in safe contexts where you must trust recent evidence, combined with cognitive techniques to consciously recognize the pattern. Professional guidance would be important.

Is this finding specific to OCD?

The mechanism appears across the obsessive-compulsive symptom spectrum, not just clinical OCD. It also appears in some people with generalized anxiety and in non-clinical individuals with OC traits. So it’s broader than just OCD diagnosis.

When will new treatments based on this be available?

Early applications could appear within 2–3 years (brain stimulation protocols, app-based training). But more robust clinical trials will take longer. The research is still in the “mechanism explanation” phase, moving toward “treatment development.”

Could this apply to other types of indecisiveness?

Possibly. Any condition involving excessive deliberation or decision-making difficulty might involve similar mechanisms. But that requires further research.

Why is the brain’s mediofrontal cortex involved in this?

This region is crucial for evaluating information, updating beliefs, and error detection. It’s been implicated in OCD before, but this research shows specifically how, by representing evidence updates less strongly. This targeted finding is more useful than knowing the general region is involved.

If people with OCD are accurate, why do they need to gather more information?

Because their brain’s updating signal is weak. Even though they eventually reach the right answer, they feel uncertain along the way, so they keep checking. Accuracy and confidence are separate systems.

Publication details

Magdalena del Río et al, Indecision and recency-weighted evidence integration in non-clinical and clinical settings, Nature Human Behaviour (2026). DOI: 10.1038/s41562-025-02385-1