Isn’t quantum computing a loneliness problem?

Not the loneliness of the researchers (though I’m sure those late nights in the lab can be isolating). I’m talking about the loneliness of quantum bits themselves. See, quantum computers are like islands, powerful, sophisticated islands, but islands nonetheless. A single quantum processor might hold thousands of qubits, which sounds impressive until you realize that the really transformative applications people dream about, the ones that could crack previously unsolvable problems, might need millions or even billions of qubits working together.

You can’t just keep cramming more atoms into a single machine. Eventually, you hit walls imposed by the fundamental laws of physics. So researchers have been working on a different approach, that is, connecting multiple smaller quantum processors together into a network, like turning isolated islands into an archipelago with bridges between them.

But to connect quantum computers, you need to read out the state of individual atoms and send that quantum information through optical fibers to other machines. And you need to do this fast and without destroying the delicate quantum states in the process. For years, scientists have been trying to figure out how to do this at scale, and they kept running into the same frustrating bottleneck.

Until now, apparently.

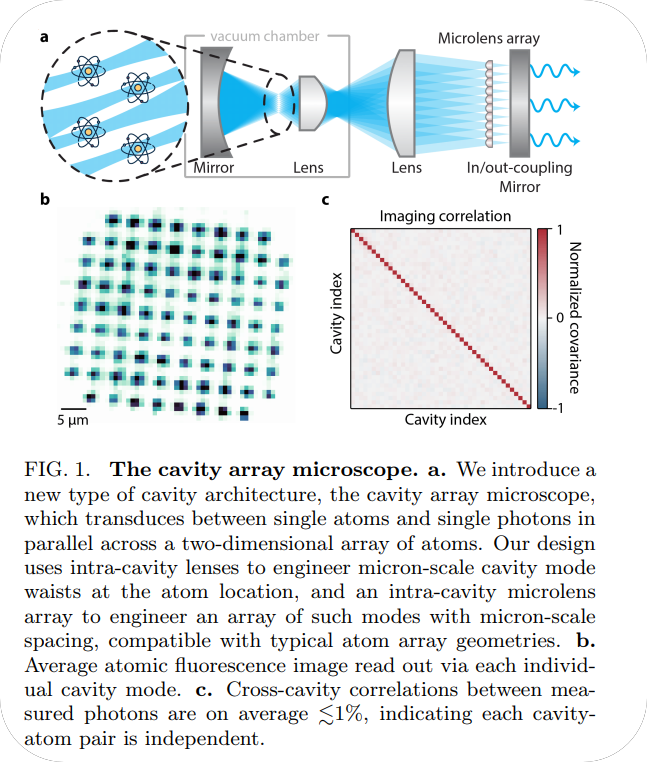

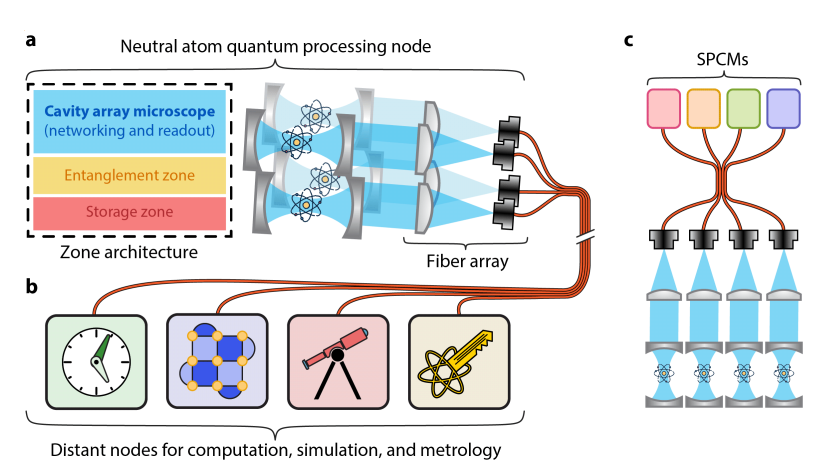

A team of researchers from Stanford, the University of Chicago, and several other institutions just unveiled the “cavity array microscope”, and it might be the missing piece that finally makes large-scale quantum networking practical. The paper, published on arXiv, describes the first entry into the “regime of many-cavity QED”, which is physicist-speak for

“we finally figured out how to give every atom its own private communication channel”.

Let me explain why that’s such a big deal, and how they pulled it off.

The Two Parallel Universes of Quantum Science

To understand what makes this work special, you need to know that quantum science has essentially been developing along two parallel tracks for decades, like two groups of explorers independently mapping different parts of the same territory.

On one track, you have neutral atom arrays.

It’s like a checkerboard made of light, where each square is an optical trap holding a single atom. Researchers can arrange hundreds or thousands of atoms in precise patterns, then use lasers to manipulate them, making them interact with their neighbors to perform quantum computations. These systems have gotten incredibly good, some experiments now achieve quantum gate fidelities approaching 99.9%, which is the kind of precision you need for practical quantum computing. One experiment even managed to wrangle nearly 10,000 atoms into a coherent array.

On the other track, you have optical cavities.

It’s like a cavity but with a tiny hall of mirrors for light. Photons bounce back and forth between mirrors, passing through the same spot over and over again. If you place an atom at just the right location inside this cavity, the repeated interactions between the atom and the same photon, making multiple passes, dramatically enhance how strongly they couple to each other. This is called “strong coupling”, and it’s incredibly useful, it makes it much easier to detect what state the atom is in, and it enables atoms to “talk” to each other through the light field.

Both approaches are powerful in their own right. Atom arrays give you exquisite control over many qubits and excellent quantum gates. Cavities give you strong light-matter coupling, which is perfect for reading out atoms or connecting them to optical fibers for networking.

So what would be the obvious next step? Combine them.

The One-Room-Schoolhouse Problem

Scientists have been trying to marry these two technologies for years, but they kept hitting a fundamental architecture problem as the “one-room-schoolhouse” problem.

Imagine you’re trying to teach a class where every student needs individual attention, but you’ve only got one room and one teacher. In the quantum version, researchers would build an atom array and then couple the entire array to a single cavity mode, one shared communication channel for all the atoms.

This creates an immediate problem, if you want to read out the state of an individual atom, you can’t do it directly. You have to either move atoms in and out of the cavity one at a time (slow and disruptive), or use auxiliary lasers to selectively activate different atoms in sequence (still serial, still slow). Either way, the time it takes scales linearly with the number of atoms, if you’ve got 1,000 atoms, you need 1,000 separate operations.

This is the opposite of parallel computing.

You’ve built this magnificent parallel quantum processor, but then when it’s time to read out the results or connect to other processors, you’re back to going one-by-one like someone reading a punch card.

What researchers really wanted was a different architecture, which is, give every atom its own individual cavity mode, its own private channel. That way you could read out all the atoms simultaneously, in parallel.

You could couple each atom to its own optical fiber for networking. You could actually take advantage of the parallelism that makes quantum computers potentially powerful in the first place.

Simple idea. Incredibly hard to execute.

The Three Big Problems You Have to Solve First

Building a two-dimensional array of optical cavities, each coupled to a single atom, with micron-scale precision, is an engineering nightmare.

First, consider the scale.

Atoms in these arrays are typically spaced just a few microns apart (a micron is a millionth of a meter, about 100 times smaller than a human hair). Your cavity modes need to match this spacing and have similarly tiny waists where they interact with the atoms. But cavities also need to be long enough to actually trap light effectively, you can’t make them arbitrarily small.

Second, there’s the problem of optical quality.

Cavities are notoriously finicky. The mirrors need to be nearly perfect, aligned to extraordinary precision. Add any optical element inside the cavity, lenses, filters, whatever, and you introduce losses, aberrations, potential points of failure. Each imperfection degrades performance.

Third, and perhaps most subtly, there’s a geometry problem.

If you try to make an array of cavity modes just by angling multiple beams into a cavity at different positions, the beams that are off-axis will accumulate errors over many round trips. Real lenses aren’t perfect, they have aberrations that cause off-axis beams to gradually walk away from their intended paths. After many bounces, these beams clip the edges of mirrors and are lost.

The Stanford team’s solution is genuinely clever, and it involves a component that surprised me when I first read about it: a microlens array, or MLA.

Just imagine, a flat piece of glass with a grid of tiny lenses on it, like a honeycomb of magnifying glasses. This optic sits inside the cavity, along with larger lenses that create a telescope system.

Now here’s the interesting part, each microlens creates a local region of stability for one cavity mode. The light doesn’t just rattle around chaotically, each beam has its own dedicated microlens that keeps it confined to a specific path, even if that path is offset from the central axis of the cavity.

The team uses a spatial light modulator (SLM) to generate an array of input beams, each precisely positioned to couple into one cavity mode. These beams pass through the intra-cavity telescope, which demagnifies them by a factor of 100. So a beam that starts with a 100-micron waist outside the cavity gets squeezed down to about 1 micron at the atom location. That’s almost exactly one wavelength of light, about as tightly focused as you can get while still maintaining a well-defined beam.

The atoms then sit at these tiny focal points. Each atom interacts primarily with its own cavity mode. The modes are independent, correlations between photons detected from different cavities are less than 1%, meaning they’re essentially not talking to each other.

The Subtle Problem of Getting Everything to Resonance Together

One of the most elegant parts of this design is how they make all the cavity modes resonate at the same frequency.

Now you might question, why does that matter? Can’t each cavity mode just have its own frequency?

Well, yes, but if you want to lock the cavity (stabilize its length against vibrations and drift) or if you want all the modes to interact with atoms at the same wavelength, you need them to be “degenerate”, aligned to the same resonant frequency.

The trick is that the team uses a 4f telescope configuration between the microlens array plane and the atom plane. In optics, a “4f system” is a specific arrangement where two lenses are separated by the sum of their focal lengths, with the object at one focal length before the first lens and the image at one focal length after the second lens. This configuration has special properties: it creates a perfect 1:1 image, and crucially, it minimizes aberrations.

By carefully adjusting the position of one of the intra-cavity lenses (they can move it with micron-scale precision), they can find the sweet spot where all the cavity modes are simultaneously resonant. When they scanned this lens position and measured the resonance frequencies of adjacent cavities, they found a clear optimum where all the peaks perfectly overlapped.

The sensitivity of this alignment scales with distance from the center of the array, modes farther from the central axis are more sensitive to lens position. But the team calculates that with sub-micron positioning accuracy (which is achievable with modern piezo actuators), you could make thousands of modes simultaneously degenerate. This scalability is crucial.

What “Strong Coupling” Means

I need to pause here and explain a concept that’s central to understanding why this work matters: cooperativity.

In cavity QED (quantum electrodynamics), cooperativity is the figure of merit that determines how well an atom and a cavity mode interact. It’s defined by two key parameters:

- Finesse (F): how many times light bounces around inside the cavity before escaping

- Mode waist (w): how tightly the light is focused where the atom sits

The smaller the mode waist, the more intense the light field at the atom location, and the stronger the interaction. The higher the finesse, the more chances the atom has to interact with the same photon on repeated passes.

The Stanford cavity array microscope achieves a cooperativity above 1, which is the threshold for “strong coupling”. This means each atom is more likely to emit a photon into its cavity mode than into free space. It means you can collect a significant fraction of the photons the atom emits. And it means you can make multiple coherent exchanges of information between atom and photon before decoherence sets in.

The team achieved this with a finesse of only about 13. That’s low by cavity QED standards, some experiments use cavities with finesses of thousands. But they compensate with an extremely small mode waist of about 1 micron. This is the whole point of their “high-NA, low-finesse” approach, by focusing the light so tightly, you don’t need ultra-high finesse to reach strong coupling.

Now the question comes, why does this matter?

Well, because high-finesse cavities are incredibly sensitive to losses. Every optical element you add inside the cavity, every lens, window, or coating, degrades the finesse significantly. By relaxing the finesse requirement, the team can introduce all the intra-cavity optics they need (lenses, microlens array, etc.) without killing the system performance. It’s a fundamentally different design philosophy.

And they’re not done improving. In a next-generation version currently under construction, they’ve already measured a finesse of over 155, more than 10 times higher, which should yield cooperativities well above 10.

Reading Atoms at Millisecond Speed

So what can you actually do with this apparatus?

The most immediate application is fast, non-destructive readout of atoms across the entire array simultaneously. And I mean truly simultaneously, not “we’ll get to each one in sequence,” but “all at once, right now.”

The team demonstrated this by illuminating all their atoms with optical molasses beams (a particular arrangement of laser beams used to cool and excite atoms). Each atom scatters fluorescence photons preferentially into its own cavity mode because of the strong coupling. These photons leak out through a partially transmissive mirror and hit a camera.

With just 4 milliseconds of exposure, they achieved an imaging fidelity of 99.2%, meaning they can correctly determine whether an atom is present or absent with 99.2% accuracy. The atom survival rate during this imaging was over 99.6%, limited mainly by the vacuum lifetime (atoms occasionally get knocked out of their traps by collisions with background gas).

Four milliseconds might not sound fast, but it’s already competitive with or better than many non-destructive imaging methods in atom array experiments. Interestingly, they estimate they could reduce this by at least 10-fold with relatively minor improvements to their collection optics. In the next-generation apparatus, with the higher finesse, they project imaging times below 100 microseconds across the entire array.

Now imagine what this enables, you could:

- run a quantum algorithm

- read out all the atoms

- reset them

- run another algorithm

all within a fraction of a second. The readout, which used to be a bottleneck, becomes almost negligible.

From Better Measurements to Distributed Quantum Computers

But fast readout is just the beginning. The real promise of this platform is quantum networking.

The researchers demonstrated a proof-of-principle by coupling four of their cavity modes to a four-channel fiber array, basically, a bundle of optical fibers with their ends arranged in a line, matched to the spacing of the cavity modes. Each cavity mode couples into its own fiber, which leads to its own single-photon detector.

This is the fundamental building block of a quantum network. Imagine you have two separate atom array quantum processors in different labs, or even different buildings. Each processor has its own cavity array microscope. When a processor finishes a computation, the cavity modes couple photons from select atoms into optical fibers. These photons travel through the fiber network, potentially over long distances, to another processor. There, they’re used to establish entanglement between atoms in the two systems.

Entanglement is the quantum correlation that allows two particles to be linked such that measuring one instantly affects the other, regardless of distance. It’s the secret sauce that makes distributed quantum computing possible. By entangling atoms in separate processors, you effectively make them part of one larger quantum computer, even though they’re physically separated.

The Stanford team’s fiber array readout maintained the same high fidelity and low cross-talk as their camera-based imaging. Crucially, it also gave them fine-grained timing information, they could watch individual atoms in real-time, see exactly when they were loaded or lost from their traps, and even identify collision events.

This temporal resolution is important for networking protocols, which often involve precise timing of photon emissions and detection events. It’s also useful for adaptive loading schemes and error correction protocols that account for atom loss.

The Key Idea That Sets This Apart From Past Work

I want to emphasize what makes this work genuinely novel, because “arrays of cavities” isn’t a new idea per se, people have built multi-mode cavities before.

The difference is addressability. Previous multi-mode cavity systems coupled many atoms to many cavity modes, creating complex collective interactions. That’s interesting for studying exotic quantum phases of matter, but it doesn’t give you individual control.

Other experiments have integrated atom arrays with nanophotonic structures, essentially, cavities built into chips using tiny waveguides and carefully engineered dielectric structures. These can achieve very small mode volumes, but they require atoms to be extremely close (nanometers) to dielectric surfaces, which causes problems. Surface charges create electric field noise that disrupts the Rydberg states used for quantum gates. Atoms can also be attracted to and stick to surfaces.

The cavity array microscope keeps atoms about a millimeter away from any dielectric surfaces—a huge distance by quantum standards. This makes it compatible with the high-fidelity Rydberg gates that atom arrays have gotten so good at. You get the benefits of strong atom-cavity coupling without sacrificing your quantum gates.

The design is also species-agnostic. The paper uses rubidium-87 atoms, but there’s nothing special about that choice. You could use other atoms—strontium, ytterbium, cesium—just by changing the wavelength of your cavity and imaging light. This flexibility is valuable because different atoms have different advantages for different applications.

Perhaps most importantly, the whole system is modular and uses mostly off-the-shelf components. The mirrors, lenses, and microlens array are commercial products. Nothing requires exotic nanofabrication or ultra-specialized coatings. This means other labs can build similar systems and potentially improve on the design relatively easily. (Well, “relatively easily” for quantum physics labs—it’s still an enormously complex experimental apparatus, but it’s not locked behind some unique fabrication capability.)

Entering the Era of Many-Cavity QED

The researchers describe their work as opening the “regime of many-cavity QED,” and I think this framing is important.

Cavity QED has been around for decades, but it’s almost always been studied in systems with one cavity, or maybe a handful. Even when experimentalists built arrays of coupled cavities to study photon physics, they typically didn’t have individual control over the atoms (or other emitters) in each cavity.

What the cavity array microscope enables is fundamentally new: a platform where you can individually control both the atoms and the cavity modes, at scale, in two dimensions. This opens up a huge parameter space for exploration.

One application they mention is engineering the Jaynes-Cummings-Hubbard Hamiltonian, which is a theoretical model describing a lattice of coupled cavities, each containing a two-level quantum system, with photons hopping between cavities. Despite nearly two decades of theoretical interest, this model has never been realized with optical photons in a large-scale 2D system. The cavity array microscope could do it.

How? By intentionally inducing cross-talk between adjacent cavity modes—basically, allowing photons to tunnel from one cavity to its neighbors. Right now, the cavities are isolated (less than 1% cross-talk), but the researchers could modify the design to couple them together in controllable ways. This would create a hybrid atom-photon quantum system with both matter and light qubits, interacting in a programmable lattice.

That’s the kind of system where genuinely new physics might emerge—quantum phase transitions, exotic correlated states, phenomena that can’t easily be studied any other way.

Takeaway

Let me zoom out to the biggest question, why does any of this matter for the future of quantum computing?

The answer is that we don’t know yet whether large-scale quantum computers will ultimately rely on networked architectures or monolithic processors. It’s possible that someone will figure out how to build a single-machine quantum computer with millions of qubits without needing to network anything.

But the networking approach has some compelling advantages.

- It’s modular, you can build smaller, more manageable pieces and connect them together.

- It’s fault-tolerant in a different way, if one module fails, you don’t lose the whole system.

- It enables distributed quantum sensing, where entangled sensors at different locations can achieve better precision than isolated sensors.

- It’s the foundation for a “quantum internet” that could enable secure communication and distributed quantum algorithms.

For all of these applications, you need to efficiently interface individual qubits with photons and send those photons through optical fibers. The cavity array microscope is a major step toward making that practical.

It’s also worth noting that quantum networking might enable applications we haven’t even imagined yet. The internet wasn’t built with social media, streaming video, or cloud computing in mind, those applications emerged once the infrastructure existed. Similarly, a quantum internet might enable applications that seem like science fiction now but become obvious in hindsight once the technology matures.

I liked that this work exemplifies a certain approach to hard problems, instead of pushing one technology to its absolute limit, find a different way to frame the problem that sidesteps the hardest constraints. It’s a reminder that progress isn’t always about scaling harder or optimizing further, sometimes it comes from stepping back, redefining the boundaries of the problem, and discovering a path that makes the “impossible” parts irrelevant.

Equally enticing is the scalability narrative. The team didn’t just build a proof-of-principle with two or three cavity modes and claim victory. They built a system with over 40 modes, characterized its performance carefully, and made concrete projections about how it could scale to thousands of modes. They thought about manufacturability, about integration with existing atom array platforms, about the practical engineering challenges of actually using this in a quantum computer.

That kind of systems-level thinking is what separates a clever idea from a technology that might actually get deployed.

Will the cavity array microscope become a standard component of future quantum computers? I have no idea. But it’s opened a door to a regime of quantum physics, many-cavity QED, that was simply inaccessible before. And historically, when scientists open new doors, they find interesting things on the other side.

I, for one, am curious to see what comes next.

Source: Science Daily & Stanford Report