There are places on the Moon that haven’t seen sunlight in over two billion years. Deep craters near the lunar south pole, their floors permanently in shadow, sit at temperatures close to -250°C. By the way, this is way colder than Pluto’s surface.

For decades, scientists have viewed these “permanently shadowed regions” mainly as potential sources of water ice. But a new proposal suggests they could be something else entirely, the perfect home for the most precise clock ever built.

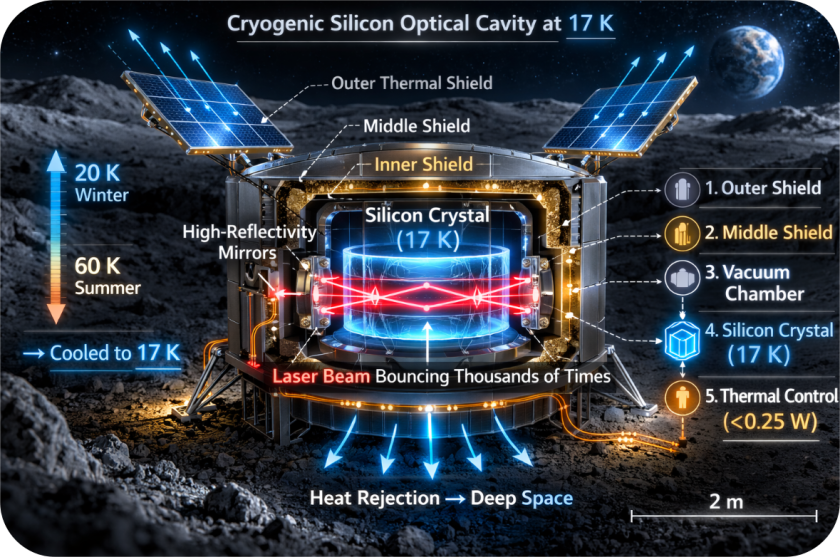

In a paper published on arXiv Lunar Silicon Cavity in February 2026, researchers lay out a detailed case for deploying a cryogenic silicon optical cavity, essentially a crystal chamber that locks a laser beam to an extraordinarily stable frequency, inside one of these eternal lunar shadows.

The result, they argue, would be a laser system so steady, so extraordinarily quiet, that it surpasses every timekeeping instrument on Earth by over a factor of ten.

If it goes well, it could be the backbone of an entirely new kind of infrastructure in space.

How Bouncing Light and Super-Cold Silicon Keep Time Perfect

Before getting into why the Moon matters, it helps to understand what this device actually does.

An optical cavity is, at its simplest, a pair of mirrors facing each other with a very precise gap in between. When a laser beam bounces back and forth between those mirrors thousands of times, its frequency gets “locked”, trained to vibrate at an exact, repeatable rate. The more perfectly stable the cavity’s length, the more perfectly stable the laser’s frequency.

It’s like tuning a guitar string. The tighter and more consistent the string, the purer and more repeatable the note. An optical cavity is doing the same thing for light, except the “string” is a beam bouncing between mirrors, and the “note” is a frequency of light used to measure time with near-supernatural precision.

The silicon part matters too. Silicon has a quirky, wonderful property, which is, at exactly 17 Kelvin (that’s -256°C), its thermal expansion coefficient drops to zero.

In simple words it means, at that temperature, the silicon crystal simply stops expanding or contracting as the temperature shifts slightly. For precision measurement, this is enormous. Most materials, even the best lab-grade glass resonators used today, are always subtly stretching and shrinking with temperature, and that movement blurs your measurement. Silicon at 17 K goes perfectly still.

The Struggle to Freeze Silicon on Earth

Physicists have actually tried building cryogenic silicon cavities in terrestrial labs, and they work brilliantly in controlled settings. The challenge is that getting silicon to 17 Kelvin on Earth is an engineering battle.

You need bulky, vibrating cryogenic refrigeration systems, acoustic isolation from the lab floor, careful vacuum chambers, and enormous energy inputs to fight entropy. Even then, residual seismic noise, acoustic vibrations from passing trucks, and the sheer difficulty of holding an ultra-stable thermal environment means performance always has a ceiling.

The current best terrestrial laser systems achieve frequency stability around 10⁻¹⁷ already staggeringly precise, capable of measuring time so accurately that losing one second would take longer than the age of the universe.

But for the next generation of physics experiments and space-based quantum networks, that’s no longer enough. The question is, where on Earth, or off it, can we do better?

Why Lunar Shadows Are Surprisingly Friendly

This is where the permanently shadowed regions become genuinely exciting. NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter has monitored temperatures in these craters for over a decade. What it found is almost paradoxical, the most remote and hostile places on the Moon are also, for an optical physicist, unusually hospitable.

The ambient temperature inside a PSR ranges from about 20 Kelvin in winter to 60 Kelvin in summer. That’s already close to silicon’s magic temperature.

Using two radiators pointed toward deep space, the same passive cooling strategy used by the James Webb Space Telescope, the research team calculates they can cool a silicon cavity system down to 17 K without any noisy mechanical refrigerators.

No vibrations.

No cryogenic fluids.

Just the cold of space itself doing the work.

Meanwhile, the lunar surface is seismically quieter than any laboratory on Earth by orders of magnitude. There are no highways, no thunderstorms, no ocean waves, no neighbors. The vacuum on the lunar surface is also far better than anything achievable in most labs.

You don’t need elaborate vacuum pumps, the Moon provides. Put it all together, and the environment that looks devastatingly hostile to a human explorer turns out to be almost tailor-made for precision measurement.

Ten Times More Precise Than the Age of the Universe

The paper’s headline figure is a thermal noise-limited frequency stability of 10⁻¹⁸. If 10⁻¹⁷ (the current Earth record) is hard to visualize, 10⁻¹⁸ is harder still. Here’s one way to think about it, imagine a clock that only loses one second every 30 billion years, roughly twice the age of the universe. Now make that clock ten times more precise. That’s the order of improvement being proposed.

The coherence time, basically how long the laser can maintain a perfectly stable phase relationship with itself, exceeds one minute.

In laser physics, this is an almost bewildering number. Today’s best Earth-based systems hold coherence for a few seconds at most. A coherent laser beam is like a perfectly synchronized wave, the longer it stays coherent, the more useful it becomes for interferometry, communications, and sensing. One minute of coherence opens doors that are currently firmly shut.

Laying the Foundation for Lunar Time and Space Networks

The researchers are clear that this isn’t just a trophy. There are real, near-term applications that such a system would enable.

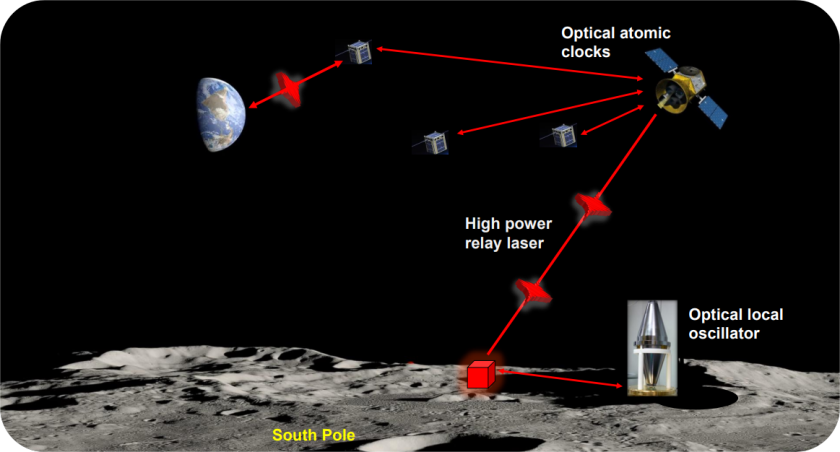

The most immediate is a lunar time standard. As humanity prepares to establish permanent infrastructure on and around the Moon, the question of how to define and distribute a common time reference has become genuinely urgent.

The Moon’s different gravitational potential relative to Earth means clocks there naturally tick at a slightly different rate, a relativistic effect that GPS satellites already have to account for here at home. A silicon cavity on the lunar surface would give any future lunar base, or any satellite in lunar orbit, access to a clock signal of breathtaking precision.

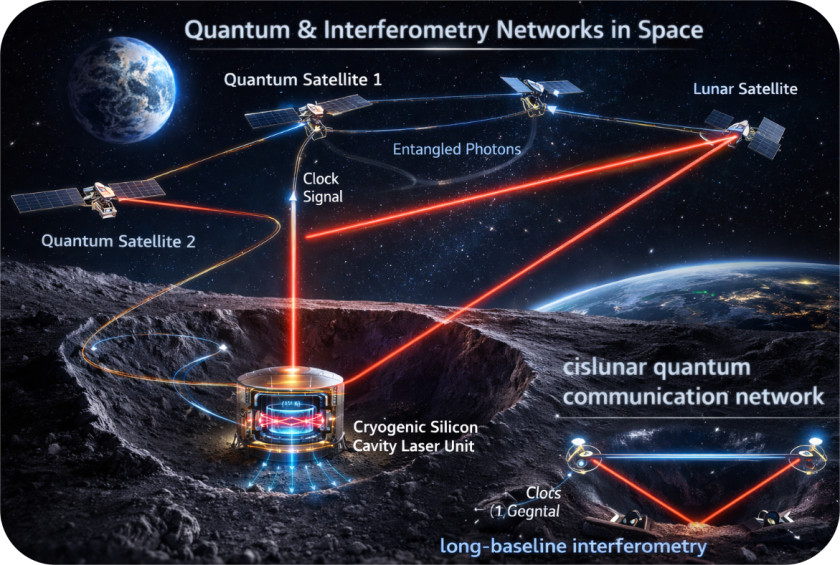

Then there’s long-baseline interferometry. Some of the most sensitive instruments in physics, gravitational wave detectors like LIGO, for instance, work by using lasers to detect the tiniest possible changes in distance between mirrors. A stable laser on the Moon could serve as one end of an interferometer stretching hundreds of thousands of kilometers, enabling gravitational wave astronomy or tests of fundamental physics at scales simply not achievable on Earth.

There’s also the idea of a space-based quantum network.

Quantum communication and computing increasingly depend on distributing quantum states across long distances, which requires maintaining the phase coherence of light beams across that distance.

A lunar silicon cavity would anchor such a network in space, serving as a kind of master reference node for satellites spread across cislunar space.

A Maintenance-Free Lab on the Moon

What’s striking about the paper is the authors’ confidence in the engineering. The biggest challenge, they note, is simply getting a silicon crystal to the Moon, the mass and volume are manageable by any future lunar lander mission.

Once on the surface, the system architecture is relatively straightforward. The thermal management scheme draws directly on heritage from missions like JWST and the far-side seismic suite deployed by China’s Chang’e-4 lander. The cavity itself sits inside three nested thermal shields; two radiators face deep space, an active thermal controller maintains the crystal at 17 K with less than a quarter of a watt of heating power.

There’s no moving machinery to vibrate.

No cryogenic fluids to run out.

No terrestrial interference to fight.

The permanently shadowed region, once the device is placed there, essentially becomes its own maintenance-free cleanroom.

The researchers describe it as a system that “will be straightforward to implement” once the material reaches the surface. For a proposal of this ambition, that’s a notable claim, and the physics backs it up.

A New Kind of Space Infrastructure

It’s worth stepping back and appreciating how this idea fits into a broader shift in how scientists think about the Moon.

For most of the space age, the Moon was conceived either as a destination for human exploration or as a platform for astronomy, a better place to put a telescope. What this proposal represents is something different:

the Moon as a laboratory environment, one whose physical properties make it uniquely suited to experiments impossible anywhere on Earth.

The permanently shadowed regions are already attracting attention for their water ice, which future missions might use to make rocket propellant or drinking water. Nearby “peaks of eternal light”, ridges just outside the shadows that receive nearly constant sunlight, provide easy access to solar power. Combine those resource advantages with the extraordinary precision measurement environment inside the craters, and you have the seeds of a genuinely useful scientific outpost.

A silicon cavity planted in that darkness wouldn’t look like much. A modest structure on the crater floor, a few radiators tilted toward the stars, a fiber-optic cable snaking out toward the sunlit ridge.

But inside, a crystal would be holding a laser beam perfectly still, more still than anything on Earth, and from that stillness would come a signal precise enough to synchronize a civilization on another world.

Making the Moon a Laboratory

This is still a proposal, not a funded mission. But it arrives at a moment when both NASA’s Artemis program and international partners are planning sustained lunar presence, which means the conversations about lunar infrastructure, power, communications, navigation, timekeeping, are happening right now.

The researchers are arguing, compellingly, that precision measurement belongs in that conversation from the start.

The physics is solid. The engineering is achievable. What’s needed now is the will to think of the Moon not just as a place to go, but as a place to think, and to measure, in ways we can’t quite manage down here.

After all, the universe’s most extreme environments have a history of becoming its most useful laboratories.

Publication details

Jun Ye et al, Lunar Silicon Cavity, arXiv (2026). DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2602.06352