In continuation of the Sensory Integration series of articles, today I will be discussing the third element of practice pertaining to Ayres’s sensory integration theory; which is her suggested treatment approach, referred to as sensory integration therapy. Ayres’s therapy techniques provide the child with various sensory experiences through play.

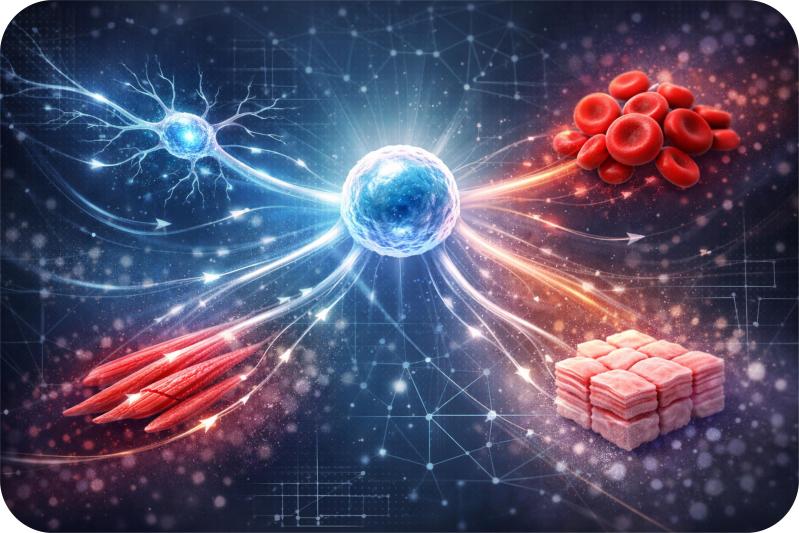

One of the basic assumptions over which Ayres’s work was constructed was that the central nervous system is plastic. Neuroplasticity refers to the brain’s ability to change or be modified. Based on this assumption, sensory integration therapy is hypothesized to cause changes in the brain (Fisher and Murray, 1991). And for families and therapists to get aspired results from such therapy techniques, intervention has to be guided through the child’s inner drive- which is another assumption underlying Ayres’s theory. Ayres supported her views with previous research which revealed that active engagement in meaningful trial-and-error learning during sensory and motor tasks induced positive biochemical changes (Miller et al., 2009). Previous research also proved that increased cortical weight and better problem solving abilities were developed in animals exposed to enriched environments when compared to ones exposed passively to sensation.

If we think about what motivates a child, the word “Fun” quickly comes to mind. In other words, the more fun it is, the more actively engaged the child will be. This makes play a key component in such therapy intervention.

In therapy, play activities are usually directed to target the three main sensory systems (tactile, proprioceptive, and vestibular). These systems are targeted for having the more primitive cortical pathways which are needed for the development of the more complex ones (i.e.: hearing, vision) (Kelly, 2008).

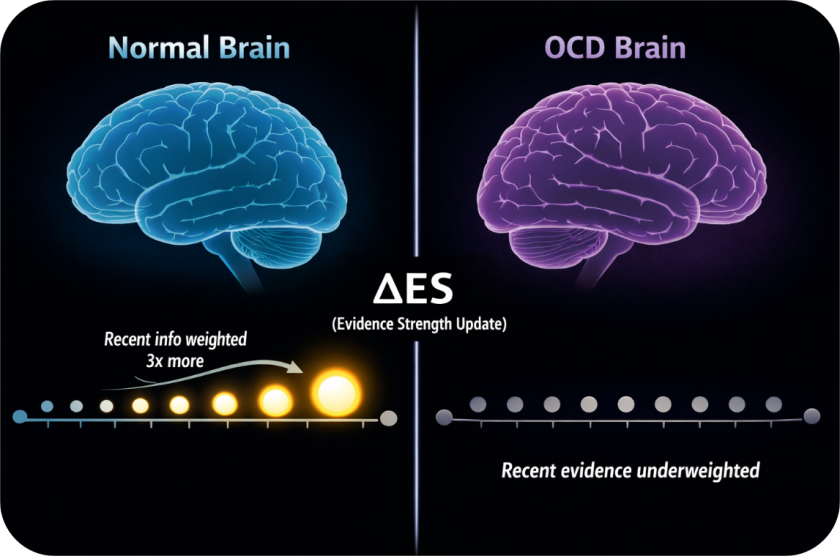

Upon the introduction of such play tasks, the child is not taught any higher level skills, but is instead expected to display active involvement in sensory experiences. Such a setting would give the child ample opportunities to experiment with different responses to presented sensory stimuli during therapy sessions. These opportunities should create new neural pathways in the child’s plastic brain (Hebb, 1949), and are later on expected to be translated into adaptive responses in the child’s natural environment.

Furthermore, Ayres also explained that potential for change is more likely in young age. “identifying the deficient areas at a young age and addressing them therapeutically can enhance the individual’s opportunity for normal development.”

While it is the responsibility of the occupational therapist to plan for the therapy intervention with regards to the above mentioned, it is also the responsibility of the parents to educate themselves, get involved in therapy, and ensure continuation of therapy into the home environment.

The more parents know, the better able they are to stay involved in their child’s therapy. Parents can educate themselves through attending workshops on the subject. A lot of professionals in the field hold such seminars and webinars and direct them specifically to parents of children with sensory integration dysfunction.

Make sure you attend sessions with your child from time to time. Ask your therapist for tips on activities that could be done at home to help your child regulate his/her sensory systems in a natural and fun way. Therapists could help through writing down a specific sensory diet for your child to be carried out at home. A sensory diet is a home programme containing suggested activities that could be done in the home environment throughout the day, in order to provide the child with needed sensory input.

READ, READ, READ. Books are a great source of empowerment for parents who want to learn. Following is a list of books and websites that could provide a good basis and a safe start for parents who want to read more on the subject:

1. Sensational Kids: Hope and Help for Children with Sensory Processing Disorder- Lucy Jane Miller Ph.D OTR, and Doris A. Fuller.

2. The Out-of-Sync Child – Carol Kranowitz.

3. The Out-of-Sync Child has fun: Activities for Kids with Sensory Processing Disorder- Carol Kranowitz.

4. Raising a Sensory Smart Child: The Definitive Handbook for Helping Your Child with SensoryProcessing Issues- Lindsey Biel, and Nancy Peske.

5. Sensory Integration and The Child- A.Jean Ayres.

6. SPD Foundation

7. Sensory Tools

References:

Fisher, A., Murray, E., (1991) Introduction to Sensory Integration Theory. In: Fisher, A., Murray, E. and Bundy A., Sensory Integration, Theory and Practice. United States of America. Philadelphia, F.A. Davis Company. PP: 3-26.

Hebb, D. O. (1949). Organization of Behavior. New York, NY, Wiley.

Miller L.J., Nielsen, D.M., Schoen, S.A., and Brett-Green, B.A. (2009) Perspectives on sensory processing disorder: a call for translational research. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience. 3: (22) PP: 1-12

Photo Source: Stroller Traffic