If you’ve ever wondered why time flies during vacations but crawls during awkward silences or like me if you often engage in thought experiments related to time, then you’ll surely like Dean Buonomano’s Your Brain Is a Time Machine, first published in 2017.

Dean Buonomano is a neuroscientist and professor at UCLA, known for his work on how the brain perceives and processes time. He’s considered one of the first researchers to seriously explore the brain’s internal sense of timing. His research blends neuroscience with complex systems and computational models. Along with the current book, he has also authored, Brain Bugs, it’s also in my reading list.

This is a book that tackles one of the weirdest questions we can ask, What is time? Not just from a physicist’s view or a philosopher’s notebook, but from the perspective of our brain. Interestingly, it is the very organ that experiences time.

Why “Time” Isn’t Just One Thing

Buonomano starts by clearing a few things. When we say “time”, we might mean totally different things, like:

- Natural time: the flow of events, cause and effect, the kind of time nature runs on.

- Clock time: the standardized, measured-by-machines kind of time.

- Subjective time: how time feels to us, which can get really weird.

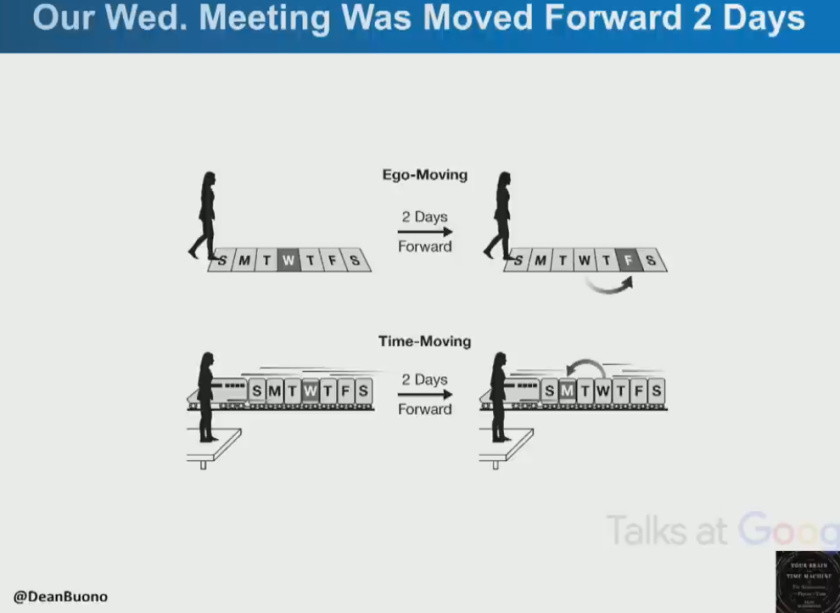

This difference matters because our brain doesn’t experience time like a stopwatch does. It’s more like thinking about the future that may or may not come true. Or at times, it is also a messy scrapbook with some missing pages, a few Polaroids with the date scribbled wrong. Talking about Polaroids, most of our memories also distort with time.

The Brain as a Time Machine

One of the book’s central arguments is that our brain is a kind of time machine, of course we are not bringing-in any sci-fiction element here. Buonomano lays down four reasons why:

- It tells time across different scales. From microseconds (important for sound localization) to circadian rhythms (like sleep-wake cycles), our brain keeps track of time on multiple levels.

- It creates the feeling that time passes. This feeling of knowing how much time has passed is like a sixth sense, and it can be misleading if we’re stressed, using drugs, or experiencing new things.

- It uses the past to predict the future. We are walking pattern detectors, constantly forecasting what comes next, even in tiny ways, like when we anticipate the next beat in a song.

- It allows for “Mental Time Travel”. We have this unique ability to re-live past experiences and imagine future ones. This isn’t just memory, it’s the ability to simulate, to plan, and to dream.

The author here stressed an important point, which is, the brain’s constant job is to model time, that is, predicting, remembering, and organizing events along a timeline. In a very real sense, that’s what consciousness is built for.

Timing Is Everything: Language, Music, and Morse Code

Chapter 5 is one of the most enjoyable. It’s all about how our brains use time to interpret patterns, especially in language and music.

Take a simple sentence, “They gave her cat food”. If you pause in the right place, it means someone gave her food that is meant for a cat. But if you move the pause slightly, it sounds like she was given a meal that looks like cat food, which might not be what you intended. This shows how much our understanding depends on the way things are said.

Same with music. If someone is playing the notes from The Beatles’ “Yellow Submarine”, but they are using the timing from “Yesterday”, it ends up sounding totally different. This shows that we’re not just responding to the actual notes or sounds, but also to the way they are spaced over time. Our brain is always busy working in the background to make sense of the rhythm and timing as we listen.

Even simple systems like Morse code depend completely on timing. A well-known example is when a captured American naval officer blinked the word “TORTURE” during a TV interview. The blinks, done in a specific rhythm, were used to send a hidden message. There were no sounds or pictures, just the pauses and quickness of the blinking.

How the Brain Actually Tells Time

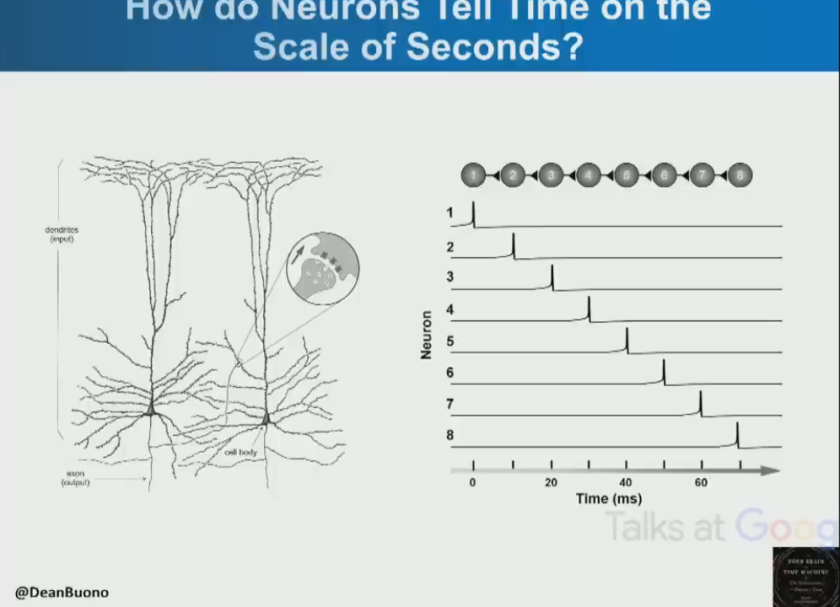

Buonomano then walks us through why the brain doesn’t use a single internal “clock”. Instead, it relies on neural dynamics, that is, changing patterns of activity in circuits.

Think of a wave of brain cells sending signals, each one causing the next to activate, kind of like a line of falling dominoes. This pattern happens over a period of time and can show how much time has gone by. It’s not like a countdown timer; instead, it’s more like a dance where where you are in the steps tells you what part of the music you’re on.

There’s another interesting research, scientists cooled the brain tissue of birds and saw that this made the birds sing more slowly. This doesn’t mean the birds are sleepy; instead, it shows that the brain’s timing controls are affected by temperature. When the brain slows down, so does the bird’s singing.

The author concluded that our brain has different systems to keep track of time for things that happen quickly, over a moderate period, or over a longer period. There’s no single internal clock that does everything perfectly. And that’s probably a good thing.

Subjective Time Is Flexible, and Sometimes Fake

Let’s get into one of the more mind-bending parts, our experience of time isn’t always real. Or rather, it’s constructed.

When we’re in a really exciting or stressful moment, like a car accident, it might seem like everything slows down. That’s not because your brain is actually working faster. Instead, your memory records all the little details, and when you remember it later, it feels like more happened or took longer than it actually did.

Buonomano then explains what he calls the “metaillusion hypothesis”, which is the idea that much of what we consciously experience, like how we perceive time passing, is actually just an illusion created by our unconscious mind. It’s not like a computer glitch or a fake reality, but more like the mind putting together a story after the fact to make sense of things.

This isn’t just a fancy or philosophical doctrine. Experiments have shown that our brains make choices really fast, within milliseconds, before we’re even aware we’ve made them. Our conscious mind might just be telling a story, putting together what just happened into a clear explanation. It’s similar to how we understand tricky or unclear sentences, depending on what words come next.

Mental Time Travel and Its Limits

The author also brings up an interesting concept of Mental Time Travel, basically the thing that allows us to picture next week’s meeting or remember last summer’s beach trip.

This ability is strongly linked to remembering specific personal experiences, things we can put in a timeline, and imagining what might happen in the future. It’s not just about recalling facts or thinking about possibilities. It’s about really re-experiencing past events and mentally practicing future ones.

But here’s the interesting part, people who have damage to certain areas of their brain, like the hippocampus, often forget things and also have trouble thinking about future events. This suggests that remembering the past and imagining the future are closely linked in how our brain works.

So What Does Physics Say? (And Why Doesn’t It Help Much)

Here’s where Buonomano shifts gears. After several chapters focused on the brain, he dives into physics and this part felt a bit off-track to me. That’s because physics, especially Einstein’s theory of relativity, suggests something totally at odds with how we experience time: that the flow of time is an illusion.

According to the theory of relativity, there’s no universal “now”. Events that are simultaneous for one person might not be for another. That idea leads to eternalism, the view that all moments in time exist equally, like slices of a block. The past and future are just as real as the present. There’s no cosmic stopwatch ticking forward.

But we don’t feel that way at all. We feel time moving forward. So where does that feeling come from?

This is where neuroscience needs to step in. If physics doesn’t fully explain how time moves forward, maybe our brains created the idea of time, just like they create our experience of color and sound, or the feeling that our body is all one connected thing.

Takeaways (and Why You Should Read This)

I especially loved the final chapters. They pull everything together, showing how the brain’s job is to weave the past, present, and future into a coherent whole. Consciousness, in a way, might be the thread that does the stitching.

Buonomano doesn’t pretend he has all the answers. But what’s refreshing is how clearly he lays out the open questions. Why do we feel time flows if physics says it doesn’t? Why did the brain evolve such a complex relationship with time? And can we ever fully trust our own temporal intuitions?

I’ve also picked-up a few pointers:

- Time isn’t just one thing. The brain handles it differently depending on context.

- We experience time based on memory and attention, not just duration.

- The brain is a prediction engine, and time is one of its most critical variables.

- Mental Time Travel might be the root of planning, storytelling, and even consciousness.

- Physics says time doesn’t “flow”, but our brains need it to.

In a nutshell, if you’re into books that blend psychology, neuroscience, and a bit of existential curiosity, this one’s worth your time.

It’s the kind of book that lingers. Long after you’ve put it down, you’ll catch yourself noticing how your mind bends time, stretching it, compressing it, jumping across it. It reminds you that we’re not just moving through time, we’re constantly shaping our experience of it, moment by moment.