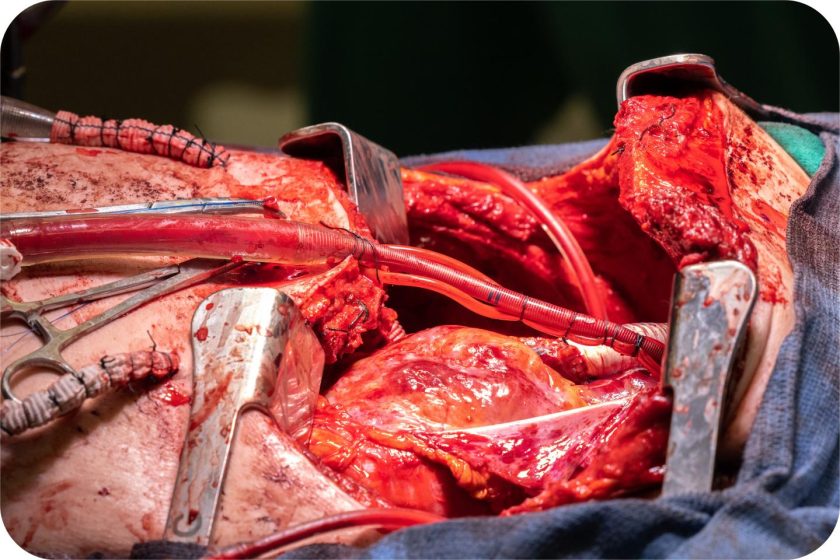

The man from Missouri should have been dead by spring 2023. By the time a medical helicopter delivered him to Northwestern Memorial Hospital on a rolling bed of tubes and machines, his body was already struggling to survive. What started as a seasonal flu had curdled into a resistant infection that was essentially melting his lungs from the inside.

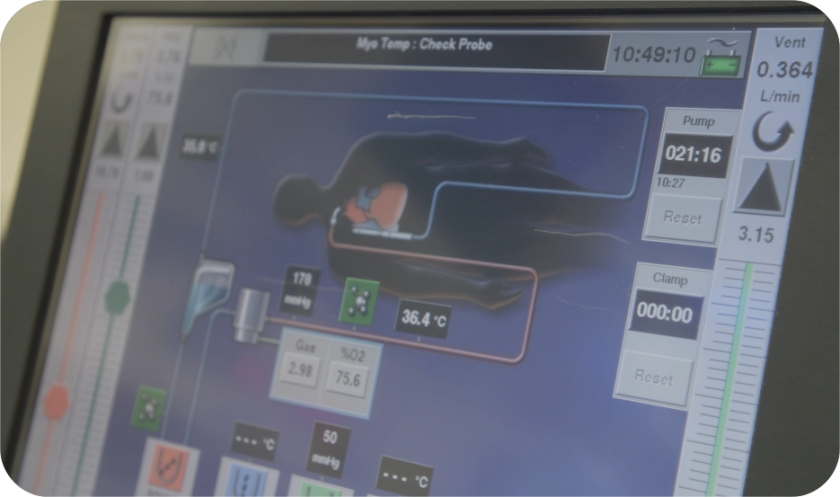

He was on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), a life-support system that pumped oxygen into his blood and kept it flowing. But the infection kept advancing. Even the antibiotics weren’t working as it was resistant to everything.

Keeping a Patient Alive With No Lungs

This patient’s lungs had become what Dr. Bharat would later describe in remarkably frank terms, liquefied. The necrotizing pneumonia, a bacterial infection resistant to virtually every antibiotic in the hospital’s arsenal, had destroyed the tissue so thoroughly that standard lung transplantation wasn’t an option. For a transplant to work, the patient needed to survive the removal of both lungs first. Dr. Bharat explained,

“He had developed an infection of his lungs that just could not be treated with any antibiotics because it was resistant to everything. That infection caused his lungs to liquify and then continued to progress to the rest of his body.”

In cases of severe ARDS (acute respiratory distress syndrome) caused by infections, doctors typically keep patients on life support and hope their lungs can heal themselves. Sometimes they do. But when the damage crosses an invisible threshold from “recoverable” to “destroyed,” hope just delays the inevitable.

Yet attempting bilateral pneumonectomy, surgical removal of both lungs, on an unstable patient seemed equally futile. Without lungs, the body loses more than just gas exchange (the ability to pick up oxygen and dump carbon dioxide). The lungs are also a critical player in circulation.

They’re a cushion in the cardiovascular system, a buffering zone that helps the heart maintain stable flow through the body’s vessels. If both lungs are removed, the heart loses its hydraulic shock absorber. Blood pressure can drop and the heart itself can collapse.

This was uncharted territory. There was no established protocol for keeping someone alive with no lungs, only a theoretical framework.

Engineering a Body’s Missing Organ

Dr. Bharat’s team didn’t have time for incrementalism. They designed what they called a “total artificial lung” (TAL) system. Standard ECMO can handle gas exchange, but it doesn’t replicate the circulatory work that biological lungs perform. The Northwestern team built something more ambitious.

Their system incorporated several ingenious features:

- A flow-adaptive shunt that mimicked the lung’s blood vessel network, the millions of tiny capillaries that normally absorb oxygen and release carbon dioxide. Without this network in place, blood would have nowhere to distribute.

- Dual drainage pathways to handle the enormous volume of blood returning from the body and needing to be reoxygenated. This wasn’t a single tube, it was a carefully engineered system to prevent blood pooling and maintain adequate return to the heart.

- Temporary internal supports to stabilize the heart’s position inside an empty chest cavity, the team used saline-filled tissue expanders, essentially breast implants, to hold space where the lungs had been and keep the heart from shifting inside the thoracic cavity.

And the overall arrangement was brilliant.

“Just one day after we took out the lungs, his body started to get better because the infection was gone”,

Dr. Bharat recalled. The removal of the infected tissue, combined with the artificial lung system maintaining circulation and oxygenation, worked. Within 48 hours, the patient’s condition had stabilized enough that the team could consider the next step: waiting for donor lungs to become available.

That window lasted two days. When suitable donor lungs arrived, the Northwestern team performed a double-lung transplant.

The Return to Life

Two years later, the patient was back living his life. Not with residual lung damage, nor was he struggling for breath or tethered to oxygen. He had excellent lung function and a second chance that seemed statistically impossible.

The case made international headlines, and deservedly so. But what might matter more in the long term was what the Northwestern team discovered when they analyzed the removed lungs at the cellular level.

What the Dead Lungs Revealed

Standard medical practice treats severe ARDS with a kind of optimistic holding pattern. Support the patient, hope the inflammation resolves, pray the tissue heals. It’s not irrational, many patients do recover but some don’t.

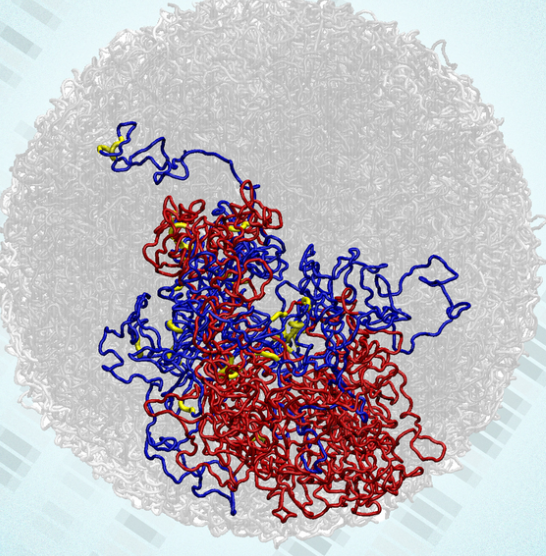

The Northwestern research team decided to look at this Missouri patient’s destroyed lungs with cutting-edge molecular biology tools that didn’t exist even five years ago. Using single-cell and spatial transcriptomic approaches, essentially, reading the genetic and protein signatures of individual cells across the tissue map, they reconstructed a portrait of catastrophic damage.

What they found was undeniable:

- extensive scarring

- immune-system damage scattered throughout the tissue

- most critically, the near-complete absence of cells that repair lung tissue

The cells that would normally rebuild damaged areas were gone. The cells that form scars were ubiquitous, while the lungs’ normal architecture had been obliterated so thoroughly that it resembled the scarred landscape of pulmonary fibrosis, an irreversible disease that kills people slowly over years. Dr. Bharat noted,

“With severe ARDS, the conventional strategy is to keep supporting the patient and hope the lungs improve. Using our approaches and data, we can show at the molecular level that some patients won’t recover unless they receive a double-lung transplant”.

This matters because it suggests a future where doctors could run similar analyses on a critically ill patient’s tissue samples and have a definitive answer to the haunting question:

“Will they get better, or am I just prolonging suffering?”

The molecular maps generated from this case are now being used to develop biomarkers and decision tools, essentially, biological signatures that would allow physicians to identify, earlier and with greater confidence, when transplantation should be considered in acute settings.

This Matters Beyond One Patient

The Northwestern case was published in Med, a high-profile journal from Cell Press, and it’s a proof of concept for several emerging ideas in critical care medicine:

First, it demonstrates that total artificial lung systems can work in the short term for patients who would otherwise have no options. The previous gold standard was hoping for recovery while the patient deteriorated. Now there’s a demonstrated alternative, controlled removal of the diseased organ followed by temporary artificial support.

Second, it points toward molecular diagnostics in acute medicine. The field has increasingly sophisticated tools for reading what’s happening in tissue at the genetic level. If those tools can identify irreversible damage in real time, they could guide treatment decisions in minutes rather than days, a significant advantage when patients are critically ill.

Third, it signals that transplantation might be a more viable option in acute settings than previously assumed. Lung transplants are typically considered only after a patient has spent weeks or months on life support, when they’ve reached a point of relative stability. This case suggests that transplantation in the acute phase of catastrophic lung failure might be feasible if you can bridge the patient from removal to transplant with adequate artificial support.

Dr. Bharat and his team acknowledge that this strategy requires extraordinary resources:

- expertise in transplantation

- extracorporeal support

- round-the-clock multidisciplinary critical care

Not every hospital can replicate what Northwestern did. But the principles, the engineering innovations, the clinical logic, the molecular insights, can be adapted. The team is now working on more standardized devices and protocols that could eventually make this approach accessible to other centers.

Medicine Becomes Engineering

What happened in that operating room at Northwestern represents something subtle but important about modern medicine. It’s increasingly becoming an interdisciplinary endeavor where surgeons, intensivists, engineers, and molecular biologists work simultaneously on the same problem, each contributing their expertise to solve something that no single discipline could address alone.

The old model of medicine was surgical:

- identify the problem

- remove it

- suture the patient closed

The new model is more like systems engineering:

- identify the problem

- devise a workaround that maintains system function during repair

- replace the broken component, then

- allow natural healing

This patient’s case is a perfect illustration of that shift. A surgeon might have looked at those liquefied lungs and said, “I can remove those”. An intensivist might have looked at the empty chest and said, “The heart will fail”. But together, with the help of engineers who designed a system to do what lungs normally do, they found a path through an impossible situation.

The techniques developed in his case are now being refined. The molecular insights from his destroyed lungs are now being used to help doctors identify other patients who might benefit from similar approaches. The artificial lung system is being standardized and simplified so other hospitals can use it.

Medical breakthroughs often look like accidents in hindsight. But this one was the opposite, it was a carefully orchestrated convergence of desperation, skill, innovation, and the willingness to attempt something that had never been successfully done before.

And it worked.

Source: Northwestern Medicine

Frequently Asked Questions

1. Where did doctors keep a patient alive without lungs?

The procedure was performed at Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago, one of the leading academic medical centers in the United States and part of Northwestern Medicine.

2. Who led the lung removal and transplant surgery at Northwestern?

The case was led by Dr. Ankit Bharat, Chief of Thoracic Surgery at Northwestern Medicine, whose team specializes in advanced lung transplantation and extracorporeal life support.

3. Has anyone survived after having both lungs removed before?

Surviving without lungs for an extended period is extraordinarily rare. This case is considered a medical first, as the patient was kept alive using a custom-built total artificial lung system before receiving a double-lung transplant.

4. What is a total artificial lung (TAL) system?

A total artificial lung system is an advanced form of life support that goes beyond standard ECMO by maintaining both oxygen exchange and circulatory stability when the lungs are completely removed.

5. Can this procedure be done at other hospitals?

Currently, this level of care requires highly specialized resources available at major centers like Northwestern Memorial Hospital in Chicago. However, the technology and protocols developed from this case are being refined so they may be adopted by other transplant centers in the future.

6. Why is this Northwestern Medicine case important for future patients?

Beyond saving one life, the case helped doctors identify molecular markers of irreversible lung damage, potentially allowing physicians to determine earlier when a lung transplant is necessary rather than prolonging ineffective treatment.