Scientists always dig deeper into the functioning of nature in order for their better understandings. At times, these trials and errors have given rise to serendipity or accidental discoveries in science, amongst others, recent being how sliding saltwater over graphene generated electricity. While at other times, these experiments go beyond the natural order of workings even at the miniscule level.

Walking on the same line of thought, researchers at The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) have bio-engineered a bacterium’s genetic makeup. They have provided an artificial DNA base to see whether the cell can replicate it like the natural DNA bases. The experts were overwhelmed when they figured out that the cell was able to bio-function effectively provided it was supplied by the building blocks from the outside.

Natural DNA

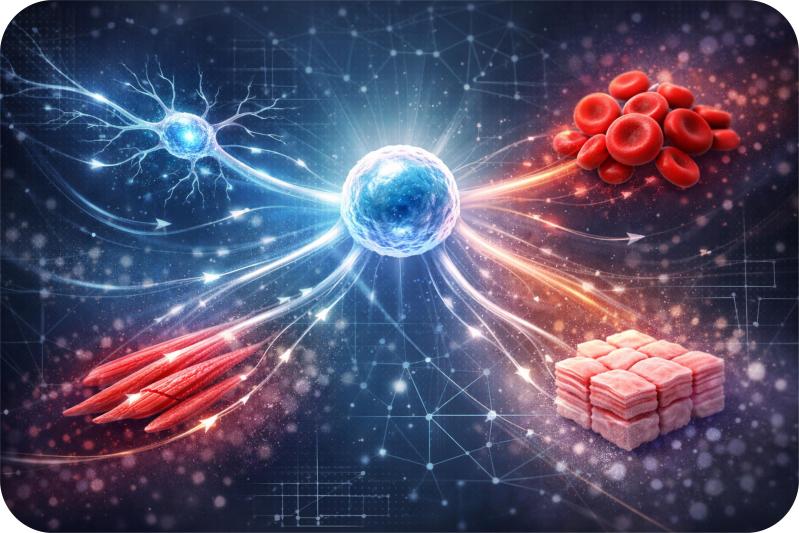

Generally, DNA exists in only two base pairs that is, A-T and C-G (adenine–thymine and cytosine–guanine). To this natural order, the experts added a pair of external base, to which they call X-Y.

The team has been working behind this research since 1990s. They were searching for molecules that might act in the similar fashion as DNA’s base pairs. Although, this was not as easy as it looked. After all, affinity with the already existing DNA base pairs was one of the major huddles, which the team had to go through. Along with that, the new base pairs were expected to line up stably with their natural conglomerates. This included the natural way of unzipping and re-zipping during DNA replication and transcription into RNA. And during the process, these nucleoside interlopers were expected to evade the chances of being attacked and destroyed by the natural DNA-repair mechanisms.

Snuggling up with Natural DNA

After much research, in 2008, the team was able to come up with a set of nucleoside molecules that were able to fasten skillfully with the natural set of base pairs in the most proximal double-strand arrangement of DNA.

Not only this, the new pair of molecules or the base pair was able to perform the similar functions like replicating in the presence of the right enzymes.

The Right Enzymes

Then the experiment went to the next level, where the researchers started looking for the ‘right enzymes’. Soon enough, the team was able to identify the enzymes that transcribe this semi-synthetic DNA into RNA.

Since it was still at the experimental stage, the trials were performed in a test tube environment. In the test tube milieu, the experiment did fairly well and so the experts decided to work on a more complex setting, which meant performing on a living cell that happened to be common bacterium E. coli.

Replicating the Semi-Synthetic DNA

Research on the bacterium involved inserting the newly synthesized DNA into its cells. The bacterium then had the new set of DNA including the natural base pairs and two molecules known as d5SICS and dNaM or the semi-synthetic DNA.

Aim behind this experiment was to observe whether the cell of the bacterium was able to replicate the semi-synthetic DNA as a normal process or not. In order to initiate the process, the researchers introduced the ‘right enzyme’ artificially of course, into the fluid solution outside the cell.

The team observed that replication was being performed by the new set of DNA material with reasonable speed and accuracy. Neither did the process hinder the growth of the E. coli cells nor did the new pair was put aside for the repair mechanisms.

Expanded-DNA Biology

Although some people were apprehensive thinking that the new set of evolved DNA might have give rise to a new form of life, however, it did not occur. Instead, the new set of artificial base pair gives the probability of taking the control over the DNA paraphernalia. Especially when we know that, the replication and transcription can be done only in the presence of certain enzymes or the building blocks, which of course has to be transported from the outside.

Along with this, the new approach takes us to the new realm of expanded DNA biology where it could be seen paving its way into medications and new forms of nanotechnology.

Source: Phys.org