I’m always on the lookout for some radical take when it comes to research papers, and this time, a research article by physicist Melvin Vopson totally caught my attention.

Vopson suggests, what if gravity isn’t some deep, fundamental force of nature, but actually just the universe’s way of managing its information better? Sounds strange at first, but it’s got a logic to it.

The Physics of Information

The core of the argument comes from two main ideas he’s been developing.

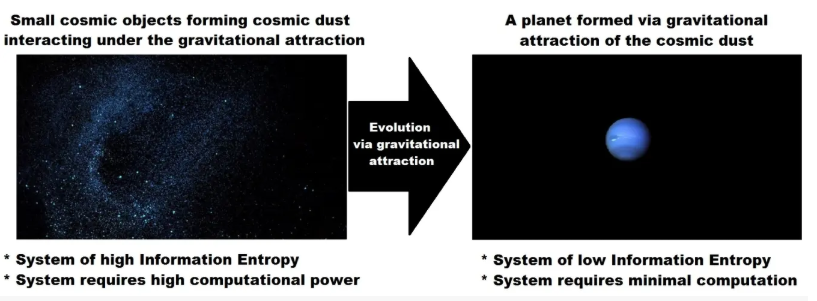

First, there’s this thing he calls the second law of infodynamics. It’s kind of like the second law of thermodynamics we all learned, except instead of physical entropy (like heat spreading out), this one’s about information entropy. Basically, the rule says that the amount of information disorder in an isolated system can only go down or stay the same as the system evolves. That’s the opposite of what we usually hear in physics, where things get more chaotic over time. He’s suggesting that if you think of the universe as a kind of computation, then it makes sense for it to try to simplify or compress the amount of information it needs to store.

Second, he brings in a principle he’s proposed before called mass-energy-information equivalence. It’s kind of like E=mc², but extended to include information. So mass, energy, and information are treated as different sides of the same thing. If that holds, then information isn’t just abstract, it has physical weight, so to speak.

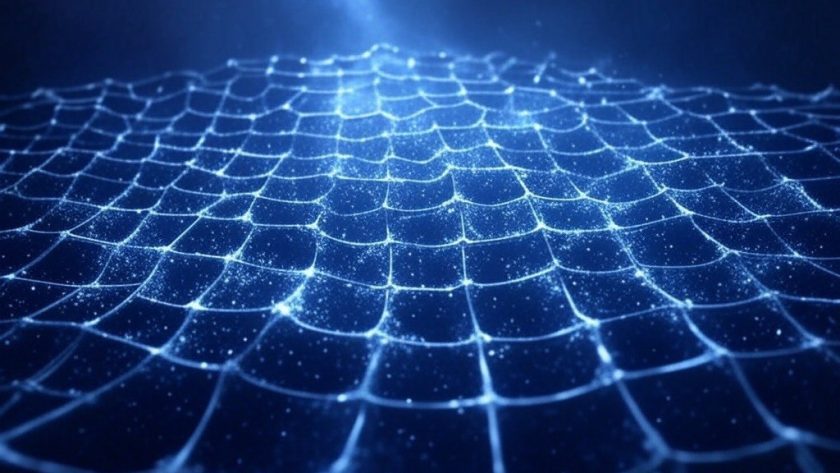

Universe Runs on Discrete Grid

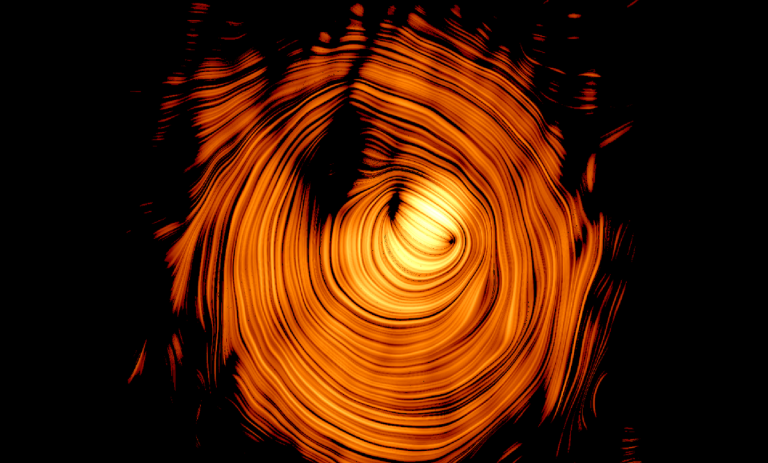

Using these two principles, he builds this picture of the universe as something that runs on a discrete grid, not smooth space-time. Think of it like pixels on a screen, but way smaller, Planck-scale small. Each little “cell” in space stores information about the matter inside it. When you drop particles into this grid, it increases the information entropy because you need more data to describe where everything is.

It’s kind of like trying to keep track of a bunch of cats in a field. If they’re all wandering around in different directions, you’ve got to constantly monitor where each one is, more effort, more data, higher entropy. But if all the cats decide to curl up in one big pile in the middle, suddenly your job’s a lot easier. One cluster, one location to watch. Same number of cats, but way less information to manage. In this theory, the universe “wants” that cat pile, it shifts toward states that are easier to describe, and gravity is just what that shift looks like.

Information Entropy

He even works through the math and gets to Newton’s law of gravity from this idea of minimizing information entropy. He starts by treating the entropic force like Newton’s F=ma, then links it to how information entropy changes when particles move. There’s a bit about using the reduced Compton wavelength as the scale for how particles shift, and how the system’s temperature and mass tie into the information content. Eventually, it all simplifies down to the familiar gravitational formula:

F = G × Mm / R²

The analogy that comes to mind is zipping a massive file. Imagine trying to send a folder full of loose, messy documents, hundreds of files all over the place. It’s bulky, hard to manage, and takes a lot of bandwidth. But if you compress the folder, the system finds patterns, trims redundancy, and wraps it up neatly. The math Vopson does is like the compression algorithm – starting with messy, scattered data (particles in space), and showing how pulling them together (via an entropic force) leads to a simpler, cleaner description. Gravity, in this view, is just the “zip process” in action. And when he runs the numbers, that compression force ends up matching exactly what we know as gravity.

Takeaway

What’s cool is that this approach actually lines up with other ideas like Verlinde’s entropic gravity theory, but it takes a different route. Verlinde talks about holographic screens and gravity coming from changes in information on those boundaries. Vopson skips the screens and says gravity comes straight from trying to reduce the total amount of information the universe has to keep track of. It’s like two people starting at different places and ending up at the same conclusion.

The paper wraps up by suggesting that if this model holds up, then gravity isn’t a fundamental force at all. It’s more like a side effect of how the universe processes information. That could have big implications for how we think about black holes, dark matter, dark energy, even the link between gravity and quantum information.

It’s kind of like how traffic patterns form in a city. Nobody builds a special force to make cars cluster at rush hour – it just happens because everyone is following basic rules (getting to work, following lights, choosing the shortest routes). The “force” of the traffic jam isn’t a thing on its own; it’s the result of millions of individual choices interacting. In the same way, gravity might not be a built-in force of nature, but something that naturally emerges from the way information gets sorted out across space.

There’s still a lot to figure out, like how this would work in full-on quantum or relativistic scenarios but it’s a fresh way to look at something we’ve taken for granted forever.

Source: University of Portsmouth