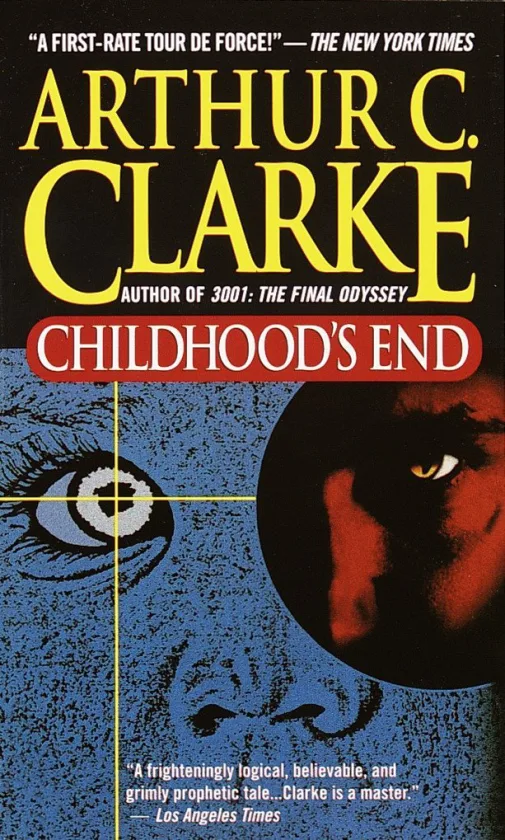

“Childhood’s End” by Arthur C. Clarke is rich in imaginative concepts and in exploration of profound philosophical and existential questions. Highly recommended by a friend, I couldn’t resist picking up this book last week. Interestingly, I initially contemplated making “2001: A Space Odyssey” my first venture into Clarke’s literary repertoire. Having completed “Childhood’s End,” I am convinced that my decision to start with this novel was a wise one.

Spoiler alert!

Set in the early 21st century (written in the 1950s), it follows a Mars mission disrupted by giant, silent spaceships appearing over major cities.

Advanced aliens, led by Karellen, aim for human unity without political boundaries. Operating through the UN, they remain unseen. Peace and prosperity prevail, but some, sceptical of the aliens, resist the perceived utopia, longing for their former imperfect freedom.

The initial utopian state created by the Overlords does involve the eradication of war, poverty, and disease, presenting a surface-level appearance of a perfect society. However, as the story unfolds, it becomes clear that this utopia is built on the surrender of individuality and self-determination.

The Overlords, as the aliens call themselves, rarely interfere with human affairs. Only twice do they involve in “earthly affair”. Firstly, addressing the oppressive white minority in post-Apartheid South Africa. And secondly, outlawing bullfighting in Spain.

They remain invisible, however, Karellen, promises to spill more information about themselves, after fifty Earth years. Stormgren, the UN Secretary General, secretly witnesses Karellen’s true form, a revelation that shocks him, but he keeps it to himself.

After five decades, humanity faces a creativity slump. The absence of conflict and struggle, combined with the Overlords’ guidance, leads to a certain complacency among humans. The society becomes stagnant, with people focusing more on leisure and comfort rather than pushing the boundaries of knowledge and creativity.

The Overlords, then, reveal their demon-like appearance and involve in psychic research. They explore the latent psychic abilities of humans and engage in experiments to better understand the potential of the human mind.

Rupert Boyce, a book collector with expertise, shares books with Overlord Rashaverak. This exchange of knowledge and information becomes a means through which humans and the Overlords connect on an intellectual level.

At one party, using a Ouija board, Boyce’s brother-in-law, Jan Rodricks, an astrophysicist, learns about the Overlords’ home star. He, then decides to stow away on an Overlord ship. Thus, embarking on a forty-light-year journey to their planet, where relativistic effects make the trip only a matter of weeks.

In the final segment, Jan Rodricks returns to Earth after about eighty years, measured in Earth time. He discovers a radically transformed planet devoid of familiar signs of humanity.

The Overmind, a powerful cosmic intelligence, has absorbed humanity into its collective consciousness, bringing about the end of individual human existence.

Jan witnesses millions of non-human-like children bound together in a trance-like existence. These children operate as a collective consciousness, serving the all-powerful Overmind, a force that even controls the Overlords themselves.

“In a soundless concussion of light, Earth’s core gave up its hoarded energies. For a little while the gravitational waves crossed and recrossed the Solar System, disturbing ever so slightly the orbits of the planets. Then the Sun’s remaining children pursued their ancient paths once more, as corks floating on a placid lake ride out the tiny ripples set in motion by a falling stone. There was nothing left of Earth. They had leached away the last atoms of its substance. It had nourished them, through the fierce moments of their inconceivable metamorphosis, as the food stored in a grain of wheat feeds the infant plant while it climbs toward the Sun.”

This portrayal highlights the evolution of humanity into a new, unified form under the influence of the Overmind.

The Overlords, unable to join the Overmind, function as a bridge between it and other evolved species. Recognizing the danger of remaining on Earth, they offer to take Rodricks with them. However, he opts to stay behind as a witness to the Earth’s inevitability.

Takeaway

Despite its relatively short length of around 250 pages, “Childhood’s End” unfolds like an impressive science fiction literature, spanning over a century in its narrative scope.

I particularly find the conversations between Stormgren and the ageless alien Karellen interesting. I’d like to highlight his memorable lines:

“It is a bitter thought, but you must face it. The planets you may one day possess. But the stars are not for Man.”

Also, the beautiful, surreal, and mind-blowing scenes within the boy’s dream resonates with the vivid and imaginative landscapes encountered by Ellie in Carl Sagan’s “Contact.”

The novel engages readers not only with its plot but also with its exploration of grand ideas about human potential and the mysteries of the universe.

Another theme that pops into my mind is questioning the viability of space as an option for humans, resonates with the current era of space exploration.

The idea that “The stars are not for Man!” challenges the prevailing optimism and echoes a sentiment that despite our advancements, there might be inherent limitations to human exploration of the cosmos.

This surely invites reflection on the complexities, uncertainties, and potential barriers that may exist as we venture further into the cosmic landscape.

In a nutshell, I thoroughly enjoyed reading “Childhood’s End” in fact it has become my second favourite after “Tau Zero” by Poul Anderson. I highly recommend to read and experience this standout work within the realm of science fiction.