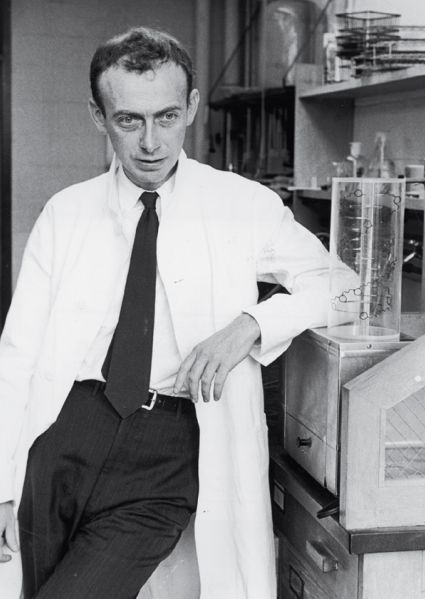

The Double Helix: A Personal Account of the Discovery of the Structure of DNA is an autobiographical version of James D. Watson in the race for DNA.

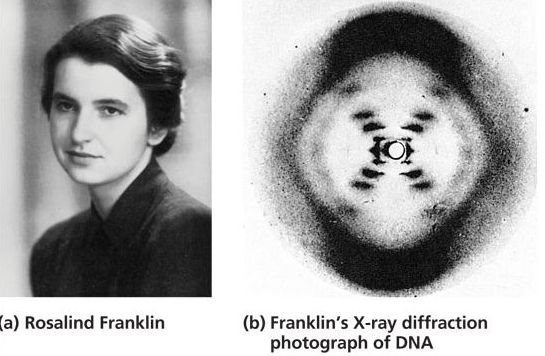

The story of the discovery of the structure of DNA is quite a read but I feel really sorry for Rosalind Franklin. Without her contribution, the men (James Watson, Francis Crick and Maurice Wilkins) wouldn’t have received the Nobel Prize.

Defaming her and other women under the hood of casual misogyny in almost entirety of the book is deeply unsettling. And by shedding some “regrets” in the epilogue can really rectify the situation, I doubt.

If Franklin hadn’t died young after suffering from cancer – may be because of excessive exposure to radiation – she would have surely received the Nobel. Nevertheless, it was her work, dedication and discovery that led to the quantum leap in the field of genetics.

The DNA journey from the eyes of Watson

As far as the book is concerned, we get to see the journey of DNA discovery from the eyes and experiences of James D. Watson, who happens to bounce around between different academia.

He first went to Copenhagen to become a biochemist. However, things didn’t go as per his expectations. He was only interested in learning more about the genetic molecule and his study was going nowhere to explore the genes.

Eventually, he goes to a meeting in Italy where he happened to meet Maurice Wilkins. Wilkins was a trained physicist but after war he did biophysics and was studying the genetic molecule in chromosome. Most people thought it was protein. But Wilkins disclosed an x-ray photograph of DNA, it showed a crystalline structure. Watson found it interesting and decided to work with him but somehow it didn’t get materialise.

From Copenhagen to England

He left Copenhagen for Cambridge, England to do research on the molecular structure of proteins. Also, because at that time the Cavendish Laboratory in the University of Cambridge was the best place for x-ray calligraphy.

His idea was to develop three-dimensional models of proteins to study them. The first person he instantaneously bonded in the Cavendish Lab was Francis Crick partially because the two happen to share common interest in studying DNA. Crick at that time was 35 while Watson was just 23 years old.

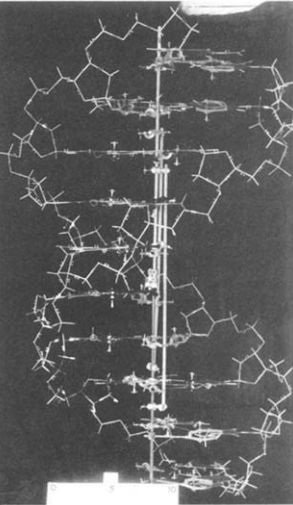

Both of them decided to build a molecular model from x-ray photographs. They were sure that by solving the molecular structure of the molecule, they would surface how genetic information is stored and passed on.

With the help of X-ray crystallography, they thought, they can solve the molecular structure. Since the technique can determine the position of every single atom in a molecule that is put under observation, with respect to other atoms of the same molecule.

Maurice Wilkins, rival researcher at the King’s College

The director of the lab however, didn’t like their idea of studying the molecular structure through X-ray crystallography, because a research group in King’s College in London was already doing similar stuff and he didn’t want to be seen as competitor.

Maurice Wilkins was working on the DNA at the King’s College. One of his colleagues, Rosalind Franklin was a skilled crystallographer. She joined the King’s College thinking that she would head the DNA research team. However, Wilkins thought otherwise. Thus, the two worked against each other.

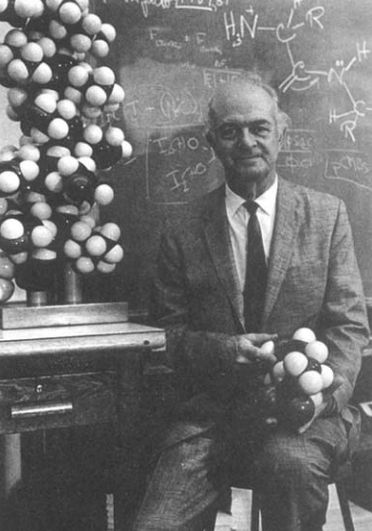

Linus Pauling, another contender in the race of DNA

In the race of DNA, not only Cambridge and London were competitors, there was in fact another equally competent person Linus Pauling from California.

Pauling was a physical chemist. He was looked up in the contemporary times for building accurate models of complex molecules. Watson and Crick were convinced that he will soon be the unanimous winner in the race.

Both – Pauling, Watson and Crick – suspected that the molecule of DNA could be a helix of some kind. Nevertheless, the mystery of sugar, phosphate and bases bonds arrangement wasn’t that easy to crack.

First “triple helix” model of DNA

After understanding the mathematics of DNA structure from Crick, Watson shuttled to London to catch up with the progress of Franklin. While talking to her, he thought that he will remember the information and so didn’t bother to make any notes. When he came back to Cambridge, he spilled all the data and together Crick and Watson started making model which they though would be of a helical molecule.

They made a structure of helix with three sugar phosphate chains on the inside and the bases sticking out. Both invited Wilkins and Franklin to take a look. Unfortunately, Watson had misremembered some of Franklin’s key measurements and therefore, the structure turned out to be a “lousy” one.

As a result, Watson and Crick were asked by the dean to not to make any more models.

For almost one full year (in 1952), both Watson and Crick read almost everything that could help in their search for DNA structure.

By next year, somewhere in 1953, they heard that Pauling was preparing a paper on the structure of DNA. Watson secured a copy of the manuscript, and he discovered that Pauling was proposing a triple helix. It was a relief because similar structure was developed by Watson and crick the previous year.

Franklin’s Photo 51

He then shuttled to London to inform that the DNA race is still on. However, Franklin continuous her work with no interest in his announcement. As he left her room, he met Wilkins who took him to his room and showed a picture of “Franklin’s Photo 51”. Watson recognised the diffraction pattern at once. It was a helix. At once he concluded that the structure is not a triple helix as proposed by Pauling but a “double helix”.

At the same time, Crick came across Franklin’s work, on the symmetry of DNA. This led to an insight which she had however missed. The two-helix had to run in opposite directions. Thus, he concluded that sugar phosphate bonds had to be on the outside with bases inside. The model was just the opposite of what they had built a few years ago.

Immediately, Watson started building the model again and this time he paired adenine with adenine, thymine with thymine and so on. Thus, making the chain identical. And this according to him could explain how genetic information is stored.

A scientist in Cambridge told him that bases could not pair themselves that way. The new model made by Crick and Watson ignored something about the DNA.

Odd results of Chargaff

A couple of years earlier, in 1950, Erwin Chargaff – an Austro-Hungarian-born American biochemist, writer, Bukovinian Jew who emigrated to the United States during the Nazi era – reported that the ratios of adenine (A) to thymine (T) and guanine (G) to cytosine (C) are equal. This later became known as the first of Chargaff’s rules.

The DNA of some organisms had an excess of A and T, while in other forms of life there was an excess of G and C. At that time no one figured out what the newly discovered base ratios meant.

Initially this information didn’t ring any bell to Crick.

“Soon afterwards, however, the suspicion that the regularities were important clicked inside his head as the result of several conversations with the young theoretical chemist John Griffith.”

The arrangement of bases

Keeping Chargaff’s data in mind, Watson went to the lab one Saturday morning on February 28, 1953. There he started playing with carboard cut-outs.

He started moving them around to form linked bonds, like A with T and likewise, G with C. Thus, placing them on top of the other. He knew if he kept placing the bonds one on top of the other, till the lab’s ceiling, it will still be a tiny fraction of a molecule. Hundreds of millions of these base pairs in one molecule.

The model perfectly fit the measurements both from the X-ray diffraction pictures and Chargaff’s data. The arrangement of bases eventually revealed how DNA works.

The complementary nature of the bases was one of the main aspects of the structure, that is, the bigger nucleotide base was pairing up with a smaller base. It also meant that the two helixes can be separated and can easily make a new complimentary copy by just obeying the pairing rules.

Therefore, the structure surfaced two things:

1) How genetic information is stored – by the sequence of the bases

2) How alteration or mutations happen – when the sequence is changed

Finally, after 9 years, Watson, Crick and Wilkins were awarded Nobel Prize for their discovery of the molecular structure of DNA.

Takeaway

In the epilogue Watson offers regrets for his portrayal of Rosalind Franklin. He apologised but after her death. Period.

He admits that both he and Crick:

came to appreciate greatly her personal honesty and generosity, realizing years too late the struggles that the intelligent woman faces to be accepted by a scientific world which often regards women as mere diversions from serious thinking.

Unlike other great scientific autobiographies, this book is full of gossip, mind games, scheming, deep unappreciation, and misogyny. Over all, the book does ensnare readers into the drama of the timelines, between personalities of the contemporary scientists and academia. It was indeed a tough time, especially if one is a woman in men dominated scientific research field.

After finishing this book, I gravitate more towards reading Rosalind Franklin: The Dark Lady of DNA. After all, the advancements of Franklin were eons ahead of her time.

[…] Watson-Crick double-helix model of DNA isn’t the whole story […]