Scientists and researchers are my intellectual heroes. I’ve spent years reading their papers, following their work, running a science and tech website that tracks breakthrough research. And in between, I’ll admit, I used to wonder what they actually do when they’re not thinking about science.

I know, I’m stereotyping them by reducing brilliant minds to lab coats and equations. But the question nagged at me. Do they cook? Do they dance? Do they binge-watch terrible reality TV? Or is their brain just permanently set to “research mode”, even while grocery shopping?

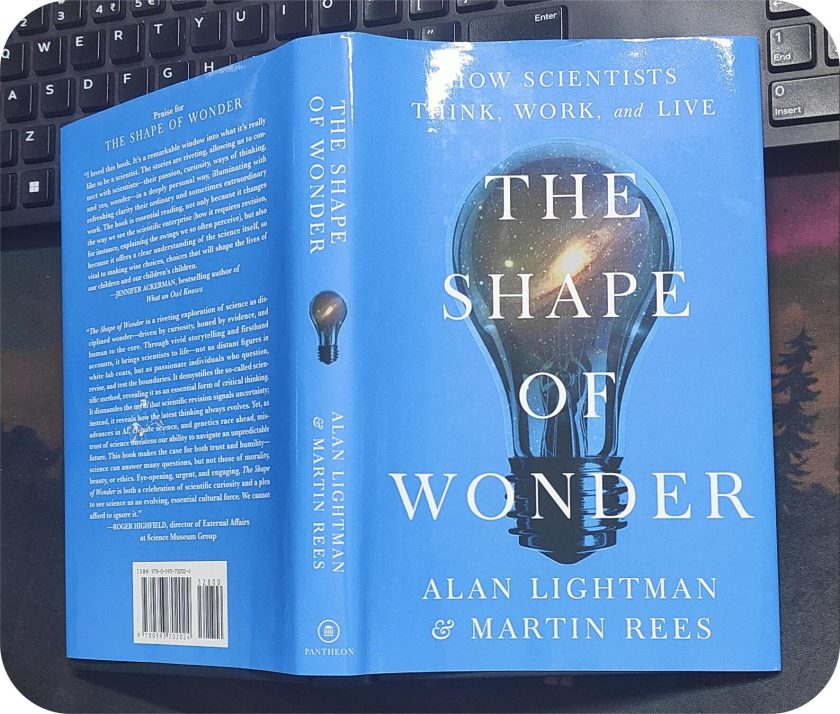

So when the publisher sent me a copy of The Shape of Wonder by Alan Lightman and Martin Rees, the timing felt almost uncanny. Here I was, running a website dedicated to science breakthroughs, reading research papers as a hobby (yes, really), and still carrying around this oddly persistent curiosity about the humans behind the discoveries.

I was a science student through class twelve. I live and breathe this stuff. But somehow, I’d never quite seen scientists as fully three-dimensional people. This book changed that.

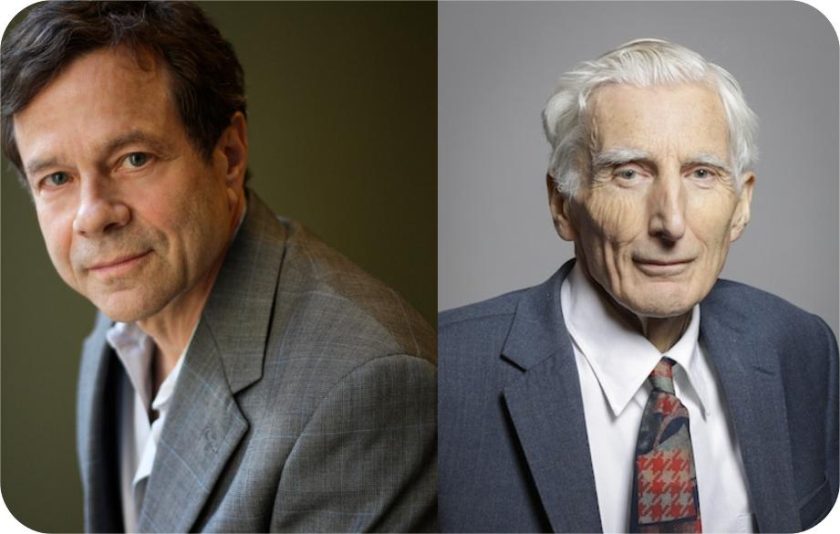

The Shape of Wonder: How Scientists Think, Work, and Live written by Alan Lightman & Martin Rees was published in 2025. Astrophysicists Martin Rees and Alan Lightman are very experienced at explaining science, not just to the public but also to people in power. Lightman now serves on the United Nations’ Scientific Advisory Board. Rees has also held many important roles, including being the Astronomer Royal for the British crown.

The People Doing the Science

I thought this book will explain why science matters, perhaps with some inspiring biographical sketches thrown in. Something along the lines of one of my favorites Richard Feynman’s Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman!, which showed us the playful side of genius. Or maybe in parallel with Walter Isaacson’s Einstein.

But The Shape of Wonder is not really about the science, it’s about the people who do science, and more specifically, about the very human motivations and contradictions that drive them.

For instance, the book introduces Lace Riggs, a neuroscientist at MIT, and traces her journey from growing up in California’s Inland Empire, marked by poverty and addiction, to a career in science. Her family moved constantly, evicted when her mother couldn’t pay rent. She studied at community college while essentially homeless.

She didn’t stumble into neuroscience from some privileged background. She chose it deliberately, driven by a realization that hit her hard, some people are more vulnerable to addiction because of their biology. If she could understand that biology, maybe she could help people like the ones she’d grown up with.

Reading about Lace in her lab, I finally got an answer to my silly question. Yes, she works long hours. Yes, she thinks about neurons constantly but she also takes out time for her jujitsu classes.

There’s No One Way to Be a Scientist

Lightman and Rees profile scientists across generations and disciplines, and what emerges is a portrait of scientific work as fundamentally emotional and artistic.

Werner Heisenberg, who revolutionized physics with quantum mechanics, was an accomplished pianist. He’d practice for hours, finding deep connections between musical harmony and mathematical structure.

Magdalena Lenda, a Polish ecologist studying invasive species, dances Argentine tango twice a week and experiments with international cooking the same way she designs field research.

Compare this to how James Gleick presented Richard Feynman in Genius, or how Sylvia Nasar portrayed John Nash in A Beautiful Mind. Those books gave us the life stories of singular geniuses, showing how their minds worked differently.

They still felt a bit separate from everyday life, as if being very smart meant being different from other people.

The book shows that scientists are just people. They are good at asking questions and are patient enough to spend many years looking for answers. Some scientists are bold and confident, like Ernest Rutherford. Others are quiet and shy, like Charles Darwin. Some work with large teams from many countries, while others work alone for many years.

The book quotes Darwin’s autobiography, where he wrote,

“I have no great quickness of apprehension or wit which is so remarkable in some clever men. I have a fair share of invention and of common sense or judgment, such as every fairly successful lawyer or doctor must have, but not I believe, in any higher degree”.

Reading this made me understand something new. The idea that scientists are “geniuses” actually causes problems. It makes science feel hard to reach, like it is only for people who are very different from normal people.

When really, as Lightman and Rees argue, the scientific method is just critical thinking applied systematically. Your mechanic uses it to diagnose your car or your doctor uses it to figure out what’s making you sick.

The Obsession Problem

But here’s where the book gets complicated, and more interesting. Because while scientists are regular humans, they’re also often obsessed humans. And that obsession is both their superpower and their vulnerability.

Barbara McClintock spent decades studying corn genetics, personally knowing every single plant in her field. She’d wake at dawn to check on them, refused to let anyone else handle them, and was famous for her extraordinary powers of observation. A colleague once said he marveled at how much she could see when looking at cells under a microscope. Her reply:

“When I look at a cell, I get down in that cell and look around”.

That level of immersion led to her Nobel Prize-winning discovery that genes could move around on chromosomes. But it also meant she worked essentially alone for years, had no close personal relationships, and faced brutal discrimination as a woman in mid-century science.

The book doesn’t romanticize this. It shows the cost of scientific obsession alongside its rewards.

Lace Riggs describes falling prey to confirmation bias, spending a year repeating a failed experiment because she was so certain of her hypothesis.

Dorota Grabowska, a theoretical physicist at CERN, talks about the “lows” of their work, days when nothing makes sense and you question whether you’re smart enough to do this at all.

How Discoveries Actually Happen

One of my favorite sections breaks down how scientific discoveries actually happen. Lightman and Rees categorize them: as,

- The Accident

- Principles First

- The Timely Clue

- The Long Haul

- The Mathematical Imperative

Alexander Fleming’s discovery of penicillin was an accident, mold contaminating his bacterial cultures. But he immediately recognized its significance because he’d been searching for antibacterial agents since medical school. The prepared mind sees what others miss.

Einstein’s relativity came from Principles First, starting with the philosophical idea that all constant-velocity reference frames are equivalent, then working out the mathematical consequences. That’s abstract thinking at its purest.

Barbara McClintock’s breakthrough came via The Timely Clue. She’d been puzzling over how genes turned on and off during corn plant development when she noticed that mutations came in pairs, neighboring leaf sections with opposite characteristics. That observation unlocked everything.

Reading this taxonomy, I thought about how science journalism often presents discoveries as sudden “Eureka!” moments. And we actually buy it, but most breakthroughs follow a pattern, which is:

- years of hard work creating a prepared mind

- getting stuck on a problem, then

- some shift in perspective or

- new piece of information that makes everything click

It’s not romantic, exactly but it’s more encouraging. Because it suggests that scientific progress isn’t about waiting for lightning to strike. It’s about doing the work, staying curious, and being ready when the pieces fall into place.

When Science Gets Uncomfortable

About halfway through, the book starts asking harder questions. This is where I really respect Lightman and Rees, they are brave enough to deal with complicated ideas.

They tell the story of Werner Heisenberg, a famous scientist who helped develop quantum mechanics and won a Nobel Prize. He stayed in Nazi Germany during World War II and worked on their atomic bomb project. After the war, he said he had purposely made mistakes so the bomb wouldn’t work. But historians aren’t sure if this is true.

The book also talks about a secret conversation between Heisenberg and his colleague Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker, which the British recorded after Hiroshima. They were thinking about whether they were responsible for what happened. Heisenberg says science itself isn’t guilty, it’s just a tool that can be used for good or bad. Weizsäcker answers that scientists can’t avoid responsibility. They have to help guide how their discoveries are used in society.

This part reminded me of Michael Lewis’s The Premonition, about scientists trying to guide pandemic policies, and Naomi Oreskes’s Merchants of Doubt, about scientists hiding climate change for money. Both books show how science and power mix. But The Shape of Wonder asks an even deeper question: What do scientists owe to society?

Lightman and Rees argue that scientists have dual responsibilities. As experts, they should inform policy on scientific matters. As citizens, they should participate in democratic life like everyone else. But they shouldn’t confuse the two roles, scientific expertise doesn’t make you an expert on ethics or policy.

I found this framework useful because, frankly, scientists often struggle with public communication. They hedge every statement with caveats. They change their minds when new evidence emerges, which confuses people who want definitive answers. During COVID, public health recommendations shifted as we learned more about the virus, and some people saw that as proof scientists didn’t know what they were doing.

But as the book explains, revision based on evidence is how science should work. You wouldn’t keep recommending a car model after discovering it had faulty brakes.

The Future That’s Coming

The final chapters tackle where we’re headed, artificial intelligence, genetic engineering, climate change, space exploration. Lightman and Rees don’t pretend to have answers. Instead, they insist these decisions must be made collectively, informed by science but guided by human values.

Within a century, we might have brain implants connecting us directly to the internet. We might edit embryos to eliminate diseases or enhance traits. We might create AI that makes autonomous decisions about our lives. We might colonize Mars and genetically modify our descendants to survive there, creating, in effect, a new species: Homo techno.

Reading this, I thought of Yuval Noah Harari’s Sapiens and Homo Deus, which explore how technology might transform humanity. But where Harari often feels deterministic, as if these changes are inevitable, The Shape of Wonder maintains agency. We choose what we build and we choose how we use it.

Takeaway

After finishing The Shape of Wonder, my silly question about what scientists do when not doing science feels almost beside the point. The real insight is simpler and more profound, scientists are us. They’re curious people who found a systematic way to satisfy that curiosity. They get excited about tiny details others ignore and they persist through failure.

Some sacrifice everything for their work, like Barbara McClintock. Others deliberately partition their lives, like Dorota Grabowska with their weekend rock climbing. Neither approach is wrong and both produce important science.

The book also clarified something I’d been sensing but couldn’t articulate. Science isn’t just a body of knowledge or a set of techniques. It’s a way of being in the world, curious, questioning, willing to change your mind when evidence demands it. That mindset doesn’t require a PhD or lab access. Anyone can cultivate it.

As someone who runs a science website, reads research papers for fun, and considers scientists my intellectual heroes, this book felt like it was written for me. It answered questions I’d been carrying around for years while raising new ones I’m still pondering.

I would surely recommend this book. Especially if you’re curious about science but intimidated by it. If you think scientists are somehow different from regular people. If you wonder how discoveries actually happen. Or if you’re worried about where technology is taking us and want to think more clearly about it.

The Shape of Wonder won’t teach you physics or biology. But it will show you the humans behind those disciplines, in all their passionate, flawed, obsessive, creative glory.

In a nut shell, Lightman and Rees say, we’re born curious and are capable of wonder. It’s in our DNA. So, maybe the real question isn’t what scientists do when they’re not doing science. Maybe it’s what the rest of us lose when we stop asking “why?”