What would the writings of Murakami be if not fiction? That question caught my attention, kind of like a loose thread dangling from an old, comfy sweater. I kept thinking about it over and over. Because if you really sit with Murakami’s novels, Kafka on The Shore, The City and Its Uncertain Walls, Norwegian Wood, A Wild Sheep Chase (currently reading) to name a few, then you’re aware of how important cats, well, metaphysical side doors, rivers, clouds, flash-backs, memories, blurring effect of reality and dreams, music, solitude are these. In fact, all these are not just imagined surreal tales in the works of Murakami, but “lived experiences”.

Have you ever thought – what would he be writing, if not these? Every writer has a style of his own, of what they return to when the world fades. And Murakami, perhaps more than anyone, writes not to escape the world but to sink deeper into its strange, forgotten corners, especially the places we pass every day but never quite see.

He has this other side of the writing style too, What I Talk About When I Talk About Running, reveals another dimension, which is a more grounded rhythm that contrasts with the dreamlike quality of his fiction. I’m still trying to understand how I truly feel about his work. Do I admire it? Does it move me the way Atwood’s writing does? With her, there’s this unmistakable depth, a sharp clarity that stirs something profound, almost unsettling, within me. When I read Atwood, I feel a kind of reverent awe, the same nervous awe a school kid might feel when the principal walks by: suddenly aware of all the ways they fall short, all the ways they’re still becoming. Her words don’t just inspire, they demand something. And that demand often leaves me questioning whether my own writing carries enough weight, enough truth, to matter.

Why I decided to read Murakami’s Running Memoir

I picked up this book – What I Talk About When I Talk About Running – for two reasons. First, that question above. And second, being a solo long-distance runner myself, I had a hunch I’d find common ground. Running, for me, is therapy with better shoes. It’s a mind reset button. And this is one of the reasons I do not listen to any playlist during long runs, the breath finds its rhythm, and eventually, the real thinking begins. Ideas bubble up on their own. Some days there are plots moving around, at times, some old memories, while other times I’m thinking about the work I do in the office, and occasionally, it’s nothing at all, and that’s beautiful too. That’s when I feel most awake.

Coming back to Murakami, this book isn’t a training log or a motivational pep talk. It’s a meditation on discipline, aging, solitude, and the strange connection between physical endurance and creative stamina. It’s quiet and modest in tone, much like Murakami himself, but laced with reflections that linger long after you’ve put it down.

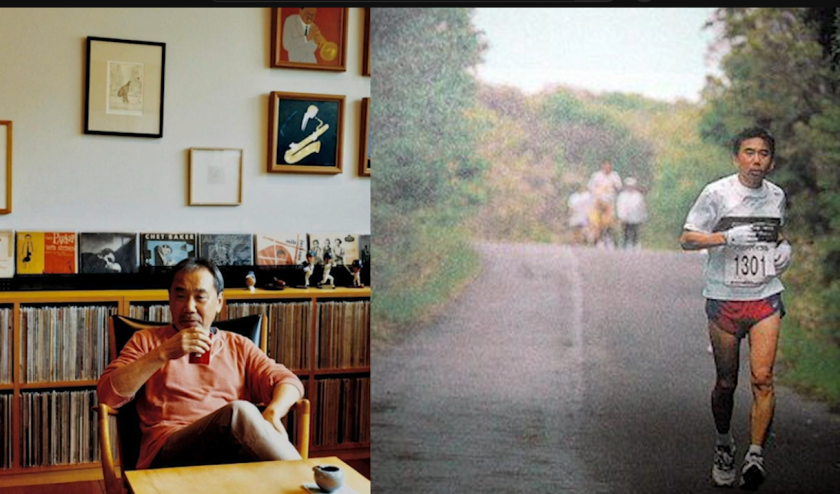

He began running in the fall of 1982, shortly after closing his Tokyo jazz bar and committing fully to writing. With the bar gone, he found himself sitting all day, smoking heavily (sixty a day), gaining weight, and losing energy. The transition from physical work to sedentary creativity forced a reckoning. He realized if he wanted to write novels for decades, he’d need to strengthen not just his mind but his body. So he took up running. Gradually, short jogs turned into daily six-mile routes. Then came marathons. Followed by triathlons.

Motion and Fatigue as Quiet Pathways Through Grief

One of my favorite things about this book is how un-dramatic his voice is. When he talks about pain, like running a 62-mile ultramarathon in Hokkaido in 1996, it’s not glorified. He describes mile 47 as hitting a wall so hard he became “a piece of machinery”. Just a body pushing itself forward, one step at a time.

It reminds me how motion and fatigue can become catalysts for working through grief. For someone facing personal loss or grief, that kind of physical endurance might not just feel familiar, it might be essential. I’ve felt it myself, when movement was the only way forward, the body moves, step by step, and somehow the heart begins to catch up.

Aging, Persistence, and Finding New Rhythms

Murakami doesn’t chase records or crowds. He runs to compete against himself, the version of him from yesterday, or last year. He trains not for glory, but for rhythm. And that’s where the deepest connection to writing lies. He draws a line between physical endurance and creative endurance, noting that talent alone won’t carry a novelist through the long haul. What matters is consistency, focus, and stamina. Just like running, writing is a way to work through feelings inside yourself. You need to come and do it, and keep at it regularly.

It’s here that I felt the strongest resonance. We often romanticize creativity, as if ideas arrive like lightning and the rest flows magically. But Murakami sees writing as a craft of slow, persistent movement. Some days feel easy and carefree, while others are tough and tiring. But you keep moving forward anyway because the act of getting there helps make you who you are and influences what you put yourself into.

His reflections on aging are just as poignant. He writes openly about declining times, persistent knee pain, and how some days, finishing the race is the only goal that matters, that’s pure honesty!

Most books either avoid that conversation or offer glossy solutions, Murakami simply accepts it. I often notice people around me who seem uneasy in their own skin, as if they’re out of sync with who they’re becoming, age wise. That’s why Murakami’s idea that the body and memory age together resonates deeply with me. It’s a reminder that growth asks us not just to keep pace, but to find new rhythms that honor both who we were and who we’re becoming.

Not Everything has to be About Being Productive

There are also other ideas, like how being alone can be important and helpful, not something to be punished for. The importance of doing simple, repeated actions, even if they don’t seem to be the most productive. Certain daily habits, like running, writing, or swimming laps, can actually help us find understanding and calm amid all the chaos around us.

And perhaps the most radical idea is that not everything has to be about being productive. Some things, like going for a run alone each morning, are valuable just because they make you feel more alive.

There’s a part where he talks about running being like being in a “void”, I call it “going into the zone” or “in flow”. It’s not about being empty or sad, but more like a peaceful mental space where all the noise and distractions disappear. I understand that feeling. Many runners do and many writers look for it, too.

So, in a nutshell, What I Talk About When I Talk About Running by Haruki Murakami is a memoir? Not exactly. A training journal? Definitely not. It feels more like a long letter from a friend you really look up to, someone who has learned how to keep going steadily, over a long period. Some of my favorite takeaways, and ones I completely resonate with, are:

- Writing and running both demand long-haul thinking.

- Focus and endurance can be cultivated, talent isn’t enough.

- Solitude isn’t absence; it’s space.

- Not all goals need to be public or competitive.

- Some discomfort is essential to personal growth.

- Routine is a form of self-respect.

If you’re someone who writes, or runs, or simply wants to understand what it means to build a life around rhythm rather than noise, this book will speak to you.